{shortcode-f689efa24a127a495816729a45b5596da0f8648c}

{shortcode-be29865d8a9c7908fa05930b7f2d42574eaa573c}n a recent video uploaded to X, Caine A. Ardayfio ’25-26 approaches a woman at Harvard’s T station. Greeting her by name, he extends a hand: “I think I met you through the Cambridge Community Foundation, right?” “Oh, yeah,” she says with a smile, rising from her seat.

In reality, the two are complete strangers. The details he knows about her personal life aren’t thanks to a shared history of volunteering, but instead have been scraped from the Internet by a pair of facial recognition glasses that Ardayfio and AnhPhu D. Nguyen ’25-26 released last month.

The spectacles — dubbed “I-XRAY” by the duo — boast the tagline: “The AI Glasses That Reveal Anyone’s Personal Details — Home Address, Name, Phone Number, and More — Just from Looking at Them.” Since posting the clip, Ardayfio and Nguyen have amassed over 20 million views. They have also caught the attention of major media outlets, thrusting them into the center of a heated public debate over the uses of facial recognition technology.

Several media outlets have framed the Harvard juniors as architects of a terrifying doxxing device. The New York Post described the pair’s software as the stuff of “every stalker’s dream.” At Forbes, the duo are “hackers.” Meanwhile, the Register, a British technology news website, points to the public nature of their device as a potential “open source intelligence privacy nightmare.”

But Ardayfio and Nguyen say that they do not intend to release their code or monetize their product. Instead, they claim I-XRAY is an “awareness campaign” that aims to publicize the dangers of facial recognition technology and improve digital privacy practices. But how do you spread awareness to the right people without feeding knowledge to the wrong ones?

{shortcode-d526042638ca9c51b83066252ae05f536fb8b384}

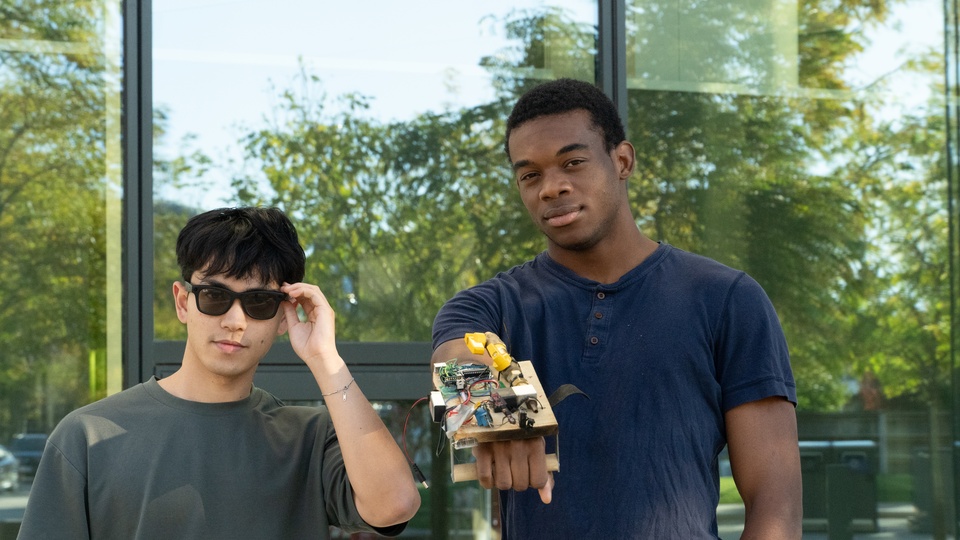

{shortcode-21cc3534b02e5a90dd1b6e61be0fe28423896a7e}rdayfio and Nguyen first met as freshmen at a makerspace, a collaborative workshop for students tinkering on side projects. At the time, Ardayfio was fixing his electric skateboard, while Nguyen had come along to work on a hoverboard.

“We were like, ‘Oh you like to build things? I also like to build things! We should build a flamethrower together,’” Ardayfio says. (Sure enough, a video they later posted to X shows Ardayfio wielding an Avengers-style flamethrower in an empty parking lot. Its caption reads: “leg hair is fully singed,” followed by a fire emoji.)

Among their other projects, Nguyen and Ardayfio have built a robotic tentacle and an electric skateboard controlled by its user’s fingers.

This year, Ardayfio and Nguyen began working on I-XRAY. As co-founders of the Harvard Virtual Reality Club, they had a pair of smart glasses equipped with cameras, open ear speakers, and a microphone. The particular model they used was a Ray-Ban and Meta collaboration that can be purchased for a few hundred dollars.

With pre-made hardware in hand, Ardayfio and Nguyen could focus on linking the glasses to their facial recognition algorithm. “The meat is in the software,” Nguyen says.

I-XRAY leverages the recording function in the smart glasses to feed video footage directly to users’ phones via an Instagram livestream. An algorithm written by Ardayfio and Nguyen then detects faces in the footage and prompts face search engines to scour the internet for matching images. If these images turn up an associated name, their software then scrapes publicly-available databases for personal data, pulling out anything from phone numbers to home addresses.

The coding took Ardayfio and Nguyen just four days. The real challenge, they say, was negotiating the ethical quandaries of releasing the video.

“We talked to quadruple the people we normally do and thought much more carefully,” Nguyen says. It took them a month to decide whether they wanted to post the video.

And no wonder: The technology behind I-XRAY already has a troubling track record. The glasses rely on PimEyes, an artificial intelligence service based in Tbilisi, Georgia, that matches online images to faces. The tool has reportedly been used to stalk women and young girls and has spurred on digital vigilantism. PimEyes itself has blocked access to its technology in 27 countries, including Iran, China, and Russia, citing worries that governments could use it to target political dissidents.

On a college campus, I-XRAY could also revolutionize social interactions. Ever overheard two strangers gossiping in a coffee shop? Ardayfio and Nguyen’s code has the potential to identify them in a matter of seconds. The same goes for anyone showing their face at a protest or rally.

{shortcode-a09c4835ddb090e0438609b7ba21591856b54d7a}

Yet the pair considers their project a net benefit for society. “Our calculation was essentially that the number of possible bad actors who would use technology like this is several orders of magnitude less than the number of people who now know that these tools exist,” Ardayfio says, adding that the latter is now in the tens of millions.

Ardayfio and Nguyen argue that their “awareness campaign” has taught people how easily others can access their personal information on the internet, challenging people’s assumptions of how they should act and whom they should trust in public.

“We think it’s best if people are straight-up aware that these things do exist,” Nguyen says. “When we talked to people before posting this, almost nobody knew what PimEyes was. Almost nobody knew you could just go from name to home address of any arbitrary person on the Internet.”

“That’s been nice: to have people know all of this exists so that you can choose to protect yourself if you do want to,” he adds.

It was important to Ardayfio and Nguyen to create adequate “guardrails” for I-XRAY. They wrote a Google Doc listing steps on how to opt out of services like PimEyes and linked it to their video. The pair hopes to highlight the potential for misuse of this technology and inspire viewers to take preemptive measures against it.

But privacy experts raise concerns about whether anyone can fully remove themselves from appearing in the results of AI search engines like PimEyes. Ardayfio and Nguyen insist you can, though they concede that other privatized engines that do not provide the opportunity to opt-out could pop up in their place.

Do they have regrets over posting the video? Ardayfio shakes his head no. “I’m very comfortable that what we did was good and right, and that it has net improved the state of security for people,” he says.

Nguyen adds that their vision is that I-XRAY will spur the government to enact policy change with regard to public databases.

Besides public awareness, Ardayfio and Nguyen envision positive applications for their glasses — most of which have garnered relatively little media attention. Nguyen suggests that wearable facial recognition technology could help emergency responders match medical records to unidentified patients. Or, as Ardayfio says, a modified version of I-XRAY could support those suffering from Alzheimers who have trouble recognizing family members.

Since their video’s success, Ardayfio and Nguyen have been invited to present their work in several Harvard courses, including Kennedy School classes on democracy and privacy. They estimate that 90 percent of the remarks they delivered were centered on the ethics of the I-XRAY glasses, rather than the technology behind them.

Looking forward, the pair says their primary goal is to have an innovative career. “We’re mostly interested in building companies, not necessarily going viral,” Nguyen says, though he admits that future ventures “may involve some component of going viral.”

For now, the juniors are still receiving media attention. They have another interview scheduled back-to-back with ours, Ardayfio reminds us as we approach our scheduled end. The pair leaves promptly to make it on time.