{shortcode-0a5bcdf3323317c43907ee1ac6367c97f6bc2c2a}

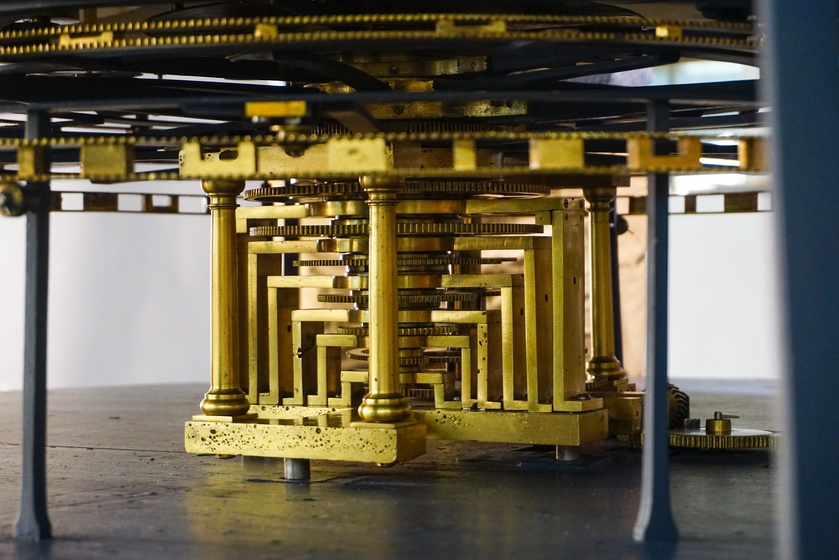

As air-conditioning billows into the Special Exhibitions Gallery on the second floor, Sara J. Schechner ’79, curator of Harvard’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, and Richard L. Ketchen, a horologist volunteering his expertise in clockmaking, huddle around a large table, their gazes fixed upon a contraption made of minute screws, sticks of metal jutting upward, and countless gears, one of which measures three feet across.

Schechner and Ketchen aren’t just here to gawk at the contraption’s complexity and beauty. The pair are finishing the monumental task of reassembling the object — the Grand Orrery — after studying each of its pieces in a disassembled form. The process is almost complete.

{shortcode-76ead7bf58dba2c8938a074a0785a257d2c51df8}

Schechner and Ketchen work together on reassembling the Grand Orrery in the Special Exhibitions Gallery of Harvard’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

Harvard acquired its Grand Orrery in 1789, two years after it was built by Boston clockmaker Joseph Pope. The device is an intricately crafted working model of the solar system made of brass, mahogany, ivory, and glass, complete with once-revolving planets, all encased under a glass dome adorned with stars. The hand-cranked orrery once vividly demonstrated the orbital paths of the first six known planets orbiting the Sun; today, the crank on the orrery no longer functions.

Although the contraption has demanded upkeep throughout the centuries, the goal of Schechner’s and Ketchen’s project is not routine maintenance but historical and scientific insights into the 18th century, involving intensive study of the materials that were sourced, how exactly they were placed together, and the way the orrery was used by various actors. This work is in anticipation of a workshop titled “Creating an Ordered World in Disordered Times: The Pope Orrery,” which will draw horologists, conservators, and a host of other specialists next November.

{shortcode-d52c2c6993ff81c7773a16f8effd4c50d799fd04}

The orrery serves as a “mise-en-scène for an examination of Boston and the British world during the American Revolution,” Schechner writes in an email. It was and is “a spectacle, prestige item, and model for teaching natural philosophy and religion,” she adds, which can reveal aspects of the state of American and British politics, economics, labor, and technology at the time.

Intricate models like this, though, weren’t typically owned by schools but by dukes, duchesses, and aristocrats — like the Earl of Orrery, whom the instrument is named after — as symbols of their education and refined taste.

Schechner explains that many craftspeople worked on the orrery. “Their tool marks are as fresh as fingerprints on the instrument,” she writes. The work of these artisans, however, was conducted under the imminent threat of conflict — the American Revolution.

“We see evidence of the war in the selection of materials used in the construction of the orrery, as well as in the political fervor that led to the statuettes of Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, and James Bowdoin (governor of the new Commonwealth of Massachusetts) on it,” Schechner wrote in an email.

The statuettes that decorate the Grand Orrery were cast by Paul Revere and include Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, James Bowdoin, and other figures.

“It’s essential to remember that the orrery is not just a model,” Associate Faculty Director of CHSI Hannah Marcus explains. “It’s a philosophically rich object that was meant to further a particular understanding of the universe.” While someone cranks the orrery to spur the model into motion, observers are moved to wonder who or what turns the “crank” of the universe.

{shortcode-1a92fdc245b8dc864064efa42fac5b37b54e939d}

As Ketchen and Schechner work on reassembly, the duo fall into near silence when placing the final screws, listening carefully to their every movement. After ensuring everything is secure, it is moved from a workshop on the second floor to its home on the first floor of the Putnam Gallery. It takes four movers to shift the main contraption from a table to a cart, through two pairs of doors, down a freight elevator, and finally into the Putnam Gallery to be reunited with its other pieces.

The Grand Orrery had to be turned on its side to fit through a door frame before being transported down a freight elevator and into the Putnam Gallery for display.

Ketchen has worked on countless clocks and instruments for the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments over the course of 30 years, but he notes that the Grand Orrery is special due to its size, history, and resilience.

{shortcode-31fd18fe69456912e385743a4fc8ae7dd8460d39}

“It went through a fire in Boston. It went through the Revolutionary War, Redcoats marching around, and who knows what they were doing with objects like this,” he explains.

“I’m glad that Harvard will take the time to keep these things up pretty much forever,” Ketchen says with a grin.

“Or we would like to think pretty much forever. Until the universe implodes, I suppose.”

— Magazine writer Ryan H. Doan-Nguyen can be reached at ryan.doannguyen@thecrimson.com.

— Magazine writer Raihana Rahman can be reached at raihana.rahman@thecrimson.com.