{shortcode-d42ef126c38b5c5fa9cb79b90606a4c19146acf1}

On the evening of Jan. 23, students erected a snow phallus in Tercentenary Theatre. At precisely 7:39 a.m. the next morning — or so claims Sidechat — a University tractor neutered the sculpture.

The entire saga was chronicled by users on the Harvard message board on Sidechat, an anonymous social media platform for college students. The news cycle started with an image of the snow penis, captioned “Cum to the yard, pretty average sized cock,” and came to a climax with a picture of the bulldozer in action, captioned “Rest in Penis - January 24, 7:39 a.m.”

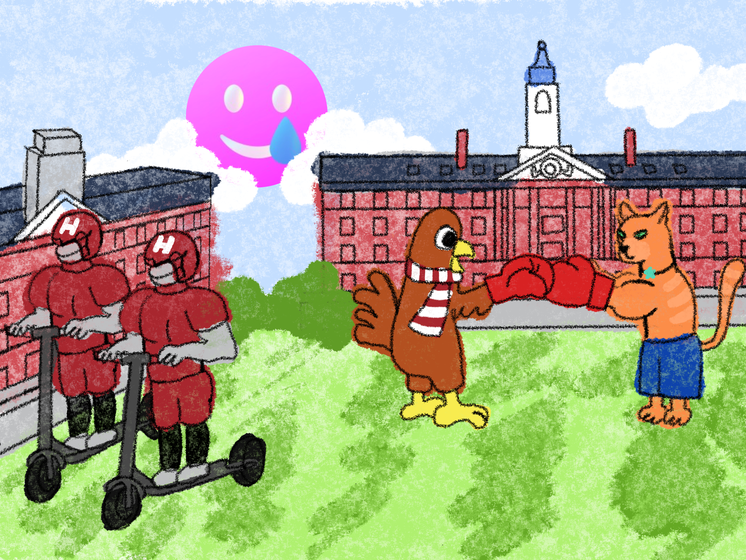

First taking off at Harvard last spring, Sidechat rapidly gained conversational relevance. Content on the app runs the gamut of Harvard life, from funny to deadly serious: digs at HUDS, rants about final club punch season, snapshots of Remy the cat being chased by turkeys, lists of “gem” classes; but also discussions about mental health struggles, sexual assault on campus, and global political events. The app’s anonymity enables users to make out-of-pocket jokes and start difficult conversations without inhibition or repercussion.

As the snow penis saga shows Sidechat bridges the gap between the physical spaces we inhabit and the Harvard that anonymous posters construct in digital spaces. Posted and upvoted on Sidechat, the snow dick is transported from Tercentenary Theatre into the theaters of our collective consciousness, marked as a mildly significant event in the daily play of college life, bringing us together into shared spaces even if we never see the sculpture with our own eyes.

Deadpan, ironic humor pervades Sidechat. The world simply feels smaller and more manageable — a Harvard akin to the university of our fantasies — when others’ goofy experiences at this large, mythic school align with our own. Sidechat allows us to imagine an institution more socially coherent than the insular circles we traverse daily. Harvard doesn’t lack communities plural so much as it lacks a unified, identifiable community, a void that Sidechat seeks to fill. And, for many, it has stepped in for The Crimson as the first source of campus-related news.

The concept of the “nation” first formed when the printing press was invented, scholar Benedict Anderson argues in his book “Imagined Communities,” because large groups of people opening the same newspaper every morning had a new sense of coexistence. Now Sidechat has, in its speed and informality, at times overshadowed student newspapers’ accounting of life at Harvard. Beautiful sunsets, cataloged on Sidechat before fading, create a sense of shared immediacy that a newspaper just can’t capture.

To be sure, there’s a good reason that The Crimson doesn’t cover every little event. Newspapers are necessary as a stable medium for nuanced discussion on political and social issues. And social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok do a better job than an anonymous platform like Sidechat at putting users in contact But unlike other platforms, where algorithms curate posts to each individual user, every Sidechat user sees the same posts in their feed, acknowledging and creating a shared experience.

Anderson calls nations “imagined communities” because “the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” Sidechat strengthens our sense of belonging within the imagined community that is Harvard College. Its posts form the elements of school myth, spirit, culture, and controversy.

Myth: classes with squads of scooters parked outside are filled with athletes and therefore must be “gems.”

Spirit: “Y’all losing your scooter privileges” was upvoted 693 times to date after Harvard lost to Yale in the Game.

Culture: “Going to Harvard gives you 4 years of inferiority complex for a lifetime of superiority complex.”

Controversy: “These frosh are making WAITLISTS for their blocking groups??? Bring bullying back fr.” These posts are familiar, funny, upsetting, and above all recognizably Harvard.

Sidechat ensures this affinity by limiting access: Users log into the app, which advertises itself as “Your college’s private community,” with their Harvard emails. Other pages on Sidechat exist for other universities. Nations are, Anderson notes, “inherently limited.” Consequently, Sidechat can have very material community-building impacts. According to Sidechat legend, people occasionally meet each other on the app’s chatboard, which allows users to have private conversations, and liaise in person. Its clear targeted audience also helps spread student-specific information and initiatives; during winter break, students promoted a GoFundMe raising money to send their roommate’s sister to high school.

This system of upvotes means that Sidechat seems quite democratic. No algorithm promotes certain posts above others; if a post appears at the top of our feeds, it’s because enough of our peers find it entertaining.

But there’s an undeniable illusion here. The top post of all time on Harvard Sidechat (an image of a student smoking next to Dean Rakesh Khurana) currently has at least 1,000 upvotes, equivalent to around one in seven Harvard undergrads. Anonymity allows individual experiences to masquerade as general public opinion so long as it has upvotes. The community formed on Harvard Sidechat is, indeed, at least partially imagined.

Anonymous platforms are, by virtue of their format, geared toward the kind of mythmaking that makes communities feel bigger and yet cohesive. School spirit is like patriotism on a smaller scale: powerful, moving, joyous, treacherous. The make-Remy-our-school-mascot movement on Sidechat is innocent, even if Remy’s supporters are beefing with the Yard turkey apologists. But, to usethe athlete-scooter myth: while funny, relatable, and potentially contains a kernel of truth, it is also at risk of causing or exacerbating tensions between segments of the student body.

Using Anderson’s ideas about nationhood to understand Harvard Sidechat means that we can use Sidechat to understand how anonymous platforms operate within America as a whole. YikYak, an app that makes anonymous discussion threads available to people within a five-mile radius of one another, is a Sidechat equivalent on other college campuses. Even on Facebook, where people are identified by name, users create “tea” pages like Harvard Confessions to anonymously post gossip that can shift quickly into bullying. Anonymous forums like 4chan and 8chan have, in the past 20 years, played an important role in our political landscape, fomenting the nationalist mythmaking movements that led to the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Sidechat and similar platforms might be constructive to the communities they represent, but they are also dangerous. It’s easy to focus on scooters and mascots, easy to ignore the conflict simmering below the surface as you scroll, and scroll, and scroll.

— Magazine writer Maren E. Wong can be reached at maren.wong@thecrimson.com.