{shortcode-6a67dfe1f86699ae356f1e8429d3dc6e03b41e45}

I felt resentful about the rain at first. It was the wreckage of my prayer for Tyre Nichols. I wanted a sunset. Dripping down the sky and skating across the horizon, for Tyre. I wanted the sun. Blanketing my grief with a divine hallelujah, spread across the skyline with an unbroken stretch of hope, reaching worlds over. Instead, we got the rain: clouded, murky, and miserable. Yet as I walked toward Tercentenary Theatre for Tyre’s vigil, I found myself resonating with the sky. She, too, was crying. She was hovering over my grief, and the grief of my people, in solidarity. Then, I wondered, why is it that even when the sky cries with me, it isn’t enough? Why is it that even when the clouds share in my anguish, the burden I carry feels no less heavy?

There is something perpetual about Black death, for me. Something claustrophobic and inescapable and choking, something unbreathable and violent and bleak. That even if all the world were to cry, even if the earth’s screams could exorcize the misery of my innocence lost so young and the heartache that comes with every Black life taken, it wouldn’t be enough. For the bullets would continue raining and the concomitant silence would drown us in the blasphemy that nothing ever happened at all.

I have felt more numbed than astonished by it as of late. In the past, to see Black death, to hear of it, was all-consuming: a wave that reached just below heaven before it came crashing down on me. I felt powerless to do anything but watch it, powerless to do anything but grieve it. And just a few feet away, I could see another wave, ready to drown me in grief all over again. It was frightening, and it was ceaseless. And such permanence and inexorability have hardened my heart.

I’ve been told not to grow weary, to shove away the whispers of exhaustion, as I would an incessant fly. I’ve been told that I don’t have time to grieve for long, that it is my obligation to fight emotional fatigue and suppress weariness. In the back of my head often buzzes the notion that if I allow my pain the liberty of being felt, it will consume me; it will slow my progress and my fervor for justice.

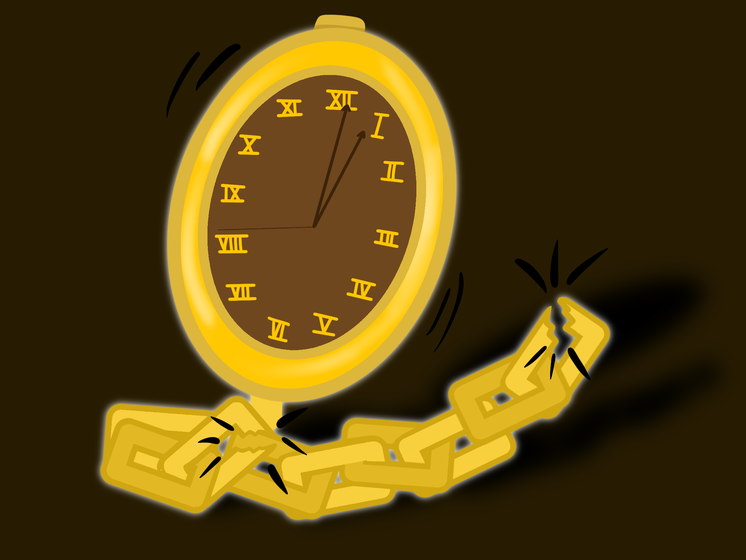

The same buzzing, I’ve found, vibrates through these ivy-covered walls — in culture, more than in law. No one has necessarily told me that I cannot feel, nor have they forced me to suppress my pain. Yet a clock seems to hang over my grief. Even at the vigil, I heard whispers of looming meetings hovering over some people, like white noise muffling the sound of their grief screaming for catharsis. They had somewhere to be, something to lead, someone they owed something. So they packaged their grief away because they felt like they had to. I wondered, then, what it would be like if even when we had to, we didn’t.

The capitalist clock, more often than not, binds my Blackness. And in times of Black grief, it dawns on me in an uncannily frightening way. The glass ceilings, built to exclude and oppress my people, have made their way into my heart and my mind. They confine my catharsis to a moment in time, my mourning to a schedule, my humanity to a transactional politic, marketed by a mass email assuring all eyes that thoughts and prayers did, or will at one point, center Black grief. And then the clock chimes, insisting the end of my grief, expecting production as usual. The violent silence prevails once again, and we wait, numbly, for the next wave to come crashing down.

But sorrow does not exit at the ring of a bell. At the closing of a ceremony, grief does not leave me. It comes in waves by nature. And in the case of Black death, the ability to suppress each wave fluctuates. Even in times of numbness, pain only lies dormant, waiting for the whispered allowance of catharsis. Or, it lies in a kind of desensitization, slowly eating away at my humanity.

Suppression is not a solution; it’s not some radicalized ideal of strength and bravery and sacrifice. It’s inauthenticity and alienation and poison. It’s claustrophobic and unbreathable and choking. It is a loss, a denial of your humanity. It is, in itself, a kind of Black death. Therefore, emotional expression is a kind of resistance; catharsis is akin to liberation. In the act of taking space to grieve, I’ve learned, is the art of welcoming my whole humanity. There, sounds the whispers of revolution.

Tyre Nichols’ vigil was a place of crying and breathing, of sharing in community even if you had nothing left to give. Our time together honoring his life closed with a song and a final word. But even after, many of us lingered. We held each other, in a sense. And we stayed, sitting in our lamentation for a little while longer. There was something powerful about that act — liberating our lingering grief.

There were points during and after the vigil, however, when it felt like people couldn’t spend any more time grieving. There seemed to be a sense that one’s schedules, plans, and meetings could not bear the weight of their healing. At that moment, I wished for time, but I also wished for strength. Strength to choose humanity whenever and wherever I could. Strength to break the capitalist clock; to paint, to write, to call my beautiful Black family; to cry, to sleep, to sit in a comforting silence; to cook, to shop, to laugh, and to laugh more. To put aside what is expected of me and liberate my lingering grief.

Grief comes in waves, by nature. And with each wave, I wish for the time to lament. I wish, also, for the strength to liberate whatever lingers when the capitalist clock chimes.

— Magazine writer Anya Sesay can be reached at anya.sesay@thecrimson.com.