{shortcode-7500d955cecc38786295ef014bf603b3e2859d86}

{shortcode-21cc3534b02e5a90dd1b6e61be0fe28423896a7e}s I sit down to interview Mira-Rose J. Kingsbury Lee ’24 in a small biology lab on the fifth floor of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, I stare at our sanitized surroundings: the gleaming gas jets, the empty vials speckling the desks. Then, of course, we begin talking about musical theater.

Kingsbury Lee, the Renaissance Person of her senior class, has written and produced three musicals at Harvard, and she’s working on a fourth: this spring’s Hasty Pudding show.

One of them, titled “Atalanta,” premiered at the Loeb Theater this spring — and was over a decade in the making.

The show, which Kingsbury Lee began writing at age eight, follows a woman in the 1960s unexpectedly catapulted into the presidency of a major newspaper, partly inspired by former Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham.

But on another level, according to Kingsbury Lee, it’s also a “naturalistic portrait of historical queerness” and an adaptation of a Greek myth from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.”

While Kingsbury Lee was inspired by Greek mythology, she tells me she “also grew up a little bit frustrated with the fact that there are not very many mothers in the Greek myths.” Atalanta’s central mother-daughter relationship subverts this trope.

Though she worked with five different orchestrators (many of them classically trained) to turn her Atalanta melodies into full musical numbers, Kingsbury Lee’s compositional skills have more modest origins. According to her, the “basis” of her musical background was drumming in a middle school rock band called “Stop Stop Playing.”

She jokes that learning to write musicals on her own is why Atalanta needed “eight or 10 years of editing.”

This lifelong labor of love culminated at the end of this summer when Kingsbury Lee brought Atalanta to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the world’s largest performance arts festival, which she calls the “holy grail” of her childhood dreams. She speaks about the experience with awe. With thousands of shows going on in locales all around the city, “there’s magic on the street all the time.”

“Because I’ve been writing it for so long,” she says, “it feels like that part of me, part of my life story, finished with the Fringe.”

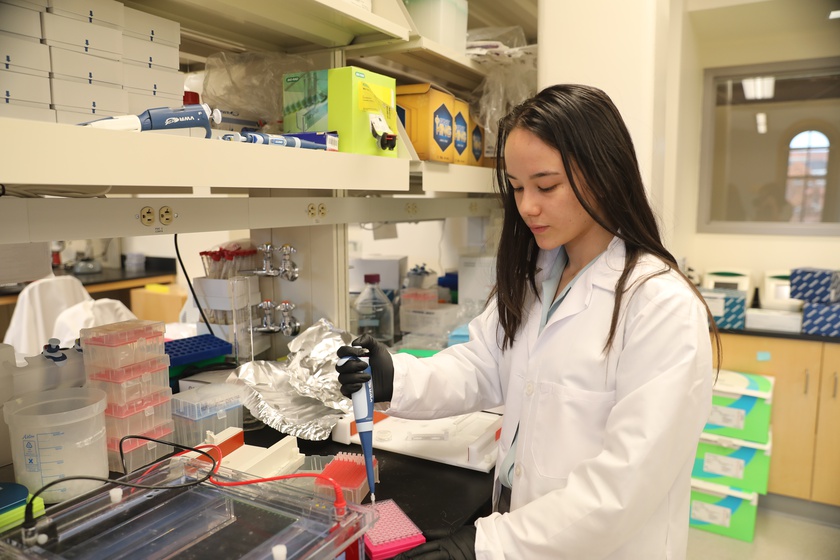

But that part of Kingsbury Lee’s life story — all those theatrical credits — says nothing about why we were meeting in a biology lab.

She has worked here since her freshman year, when she took a class on the gut microbiome with the lab’s principal investigator, Professor Rachel Carmody.

Kingsbury Lee brings the same enthusiasm to the microscopic organisms of our intestines as she does to the characters in her musicals.

Microbes “have this very unfair reputation as being pathogenic,” she tells me. “Only now we’re starting to realize that for every pathogen, there are about a billion microorganisms which are benign or even beneficial.”

She is now at work on a Human Evolutionary Biology thesis about how the post-industrial Western diet has changed humans’ gut microbiota and overall health. The relative lack of research in the field makes it “so exciting” for her. In fact, last summer, she did preliminary research for an entire nonfiction book about the history of microbes. It’s a fitting combination for a double concentrator in History and HEB.

And yet, the immensity of her time commitments does not seem to weigh on her.

“You’d be surprised at how much free time I have,” she says. Between writing and producing plays, going to class, and lab work, she spends time in organizations like Harvard Kiwis, the Salon for the Arts and Humanities, and the student astronomy club STAHR. Among her hobbies are reading, birdwatching, and climbing trees. And she sleeps — ideally nine hours per night. I only learn after our interview that she is also a member of the Advocate poetry board.

Ironically, the glut of opportunities was one of the hardest parts about college for her.

“I wish I could have met more people and done more things and stretched myself,” she says.

Luckily for her, Kingsbury Lee will have two more years to meet people and stretch herself — this time at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship.

At Oxford and beyond, she has grand hopes for her tiny organisms.

Not only did microbes help make our climate what it is today by oxygenating the planet, she tells me. “They also have this kind of enormous untapped potential to influence our climate in the future.”

Microbes can help with carbon capture, peatlands management, cleaning up contaminants, and possibly biofuel production. At Oxford, Kingsbury Lee hopes to study these applications and make them more feasible and effective.

How does theater fit into that plan?

Kingsbury Lee hopes her interests, in the future, “will be connected by this overarching theme of climate change.” For her, scientific research and creative writing can be a shared mode of effective communication.

“How do we get people to really care? To me, the answer has always been a combination of education and art,” she says.

As she explains these aspirations to me, I’m struck by another overarching theme of our conversation: gratitude.

“Everything I’m doing now is because some person or another either took me under their wing or taught me how to do something,” she says. “It’s all been through the influence of all these incredible people that I’ve been able to meet over these three and a half years or so.”

Even her interests themselves, she tells me, “have been a combination of just really extraordinary people who have influenced my life.”

As our conversation winds to a close, I ask Kingsbury Lee if she’s happy with what she’s done.

“I’m so happy with the people I’ve met,” she says. It’s the answer to a different question, but perhaps a more fitting one.

— Associate Magazine Editor Hewson Duffy can be reached at hewson.duffy@thecrimson.com.