James Hamlet Bolt Easton, class of 1883, had been a shoe-in for anchor four years in a row. There had been other anchors before him, and there would be anchors after him, but by 1887, Easton — known to be physically imposing even among athletes — had proved his reputation as a straight pipeline to victory for Harvard’s collegiate tug-of-war team.

Though tug-of-war is reserved for summer camps or family reunions today, it used to be a fiercely competitive sport, played at the collegiate and even Olympic levels. An 1887 Crimson article traces its history from its origin with sailors and navy men to its former place in the world of collegiate athletics, referring to the sport as “the most eagerly awaited event on the programme of a college athletic meeting.”

At the time, Harvard’s tug-of-war team was known as “the champion team among colleges,” according to an 1887 article in MIT’s newspaper, and had gone undefeated except for “one blot on their scutcheon.” On an unsuspecting day in March, the Harvard team’s undefeated record — and Easton’s ego — took a hit from an unlikely challenger: MIT’s ragtag tug-of-war team.

Easton, a law school student — not an unheard of addition to college athletics at the time — was credited with much of the Harvard team’s success during his 1883 to 1887 stint. Hailing from Minnesota, Easton was a Renaissance man of an athlete, lending his skill to the first Harvard lacrosse team and the second Harvard football team. But what he would become most known for was his role as tug-of-war anchor.

{shortcode-1a36b796843743819da454ab8a63122a67aa4cf3}

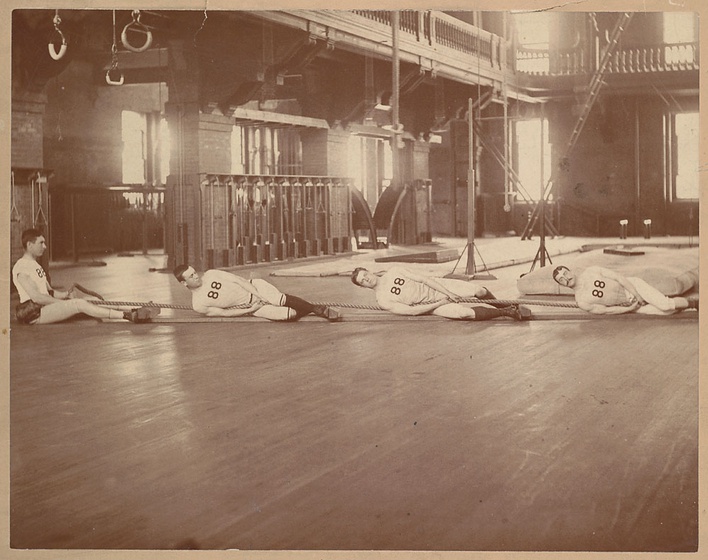

In tug-of-war, the anchor stands last in line and secures the rope. The term has also been utilized in other athletic contexts to indicate the fastest or strongest person on a team. According to an 1887 Crimson article, many strategic maneuvers used to gain an advantage in tug-of-war relied on the competence and action of the anchor.

Based on surviving records from Harvard’s archives, the fanaticism associated with the sport’s brief success seemed to have been foregrounded by Easton’s contribution. A December 1886 article reprinted from the Boston Herald described a match in New York in which “the Harvards were lying at ease on the plank, Easton alone keeping his hands on the rope.”

By contrast, the team from MIT that Harvard faced in March of 1887 had none of their prestige. Consisting of only four members and 10 pounds underweight, they had assembled at the last minute and entered the competition with only three hours of total practice and training. And they were gearing up to face a team made up of members with recent memories of victories at Mott Haven, the highly spectated New York intercollegiate competition that took place each year.

Perhaps Easton’s cleats failed, perhaps the Harvard team tried some trick maneuver out of arrogance that cost them the rope, or perhaps they weren’t as good a team as their fans on the Crimson thought they were. It’s not clear what happened in that match, but MIT managed to pull the rope two and half inches to their favor.

In the March 17 edition of its newspaper, an MIT reporter upheld the victory as “the greatest athletic feat which the Institute has ever accomplished.”

The Crimson’s article, published a few days later, took a more matter-of-fact tone: “We sent in four of our strongest men to pull against Technology, and we were fairly beaten.”

Still, the defeat caused contention among sports spectators. The article also makes reference to another previously published opinion, which the March 24 one referred to as “both extremely infantile in his arguments and ungenerous to ward [sic] the ‘Tech’ team.”

It’s not clear whether the Harvard team suffered any personal or public loss of reputation, but by January 1889, only 11 out of 300 freshmen tried out for the team. By 1891, Harvard and many other colleges had ended their tug-of-war teams altogether, presumably due to prolific injuries, contentious results, or an unsustainable smorgasbord of options for athletic participation.

As for Easton, who graduated after the 1887 season, he had driven himself to the point of near death with overwork throughout the course of his college athletic career. After college, his interests shifted as he embraced music, then race horse breeding, and eventually moved south seeking the solace of a different pace, growing citrus and sugar cane in Florida. There he died in 1921, at the age of 62, just a year after the Olympics officially removed tug-of-war from its roster.

— Magazine writer Jem K. Williams can be reached at jem.williams@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @jemkwilliams.