{shortcode-18c48e9285223d0a9720ee9196246c52c142ddb7}

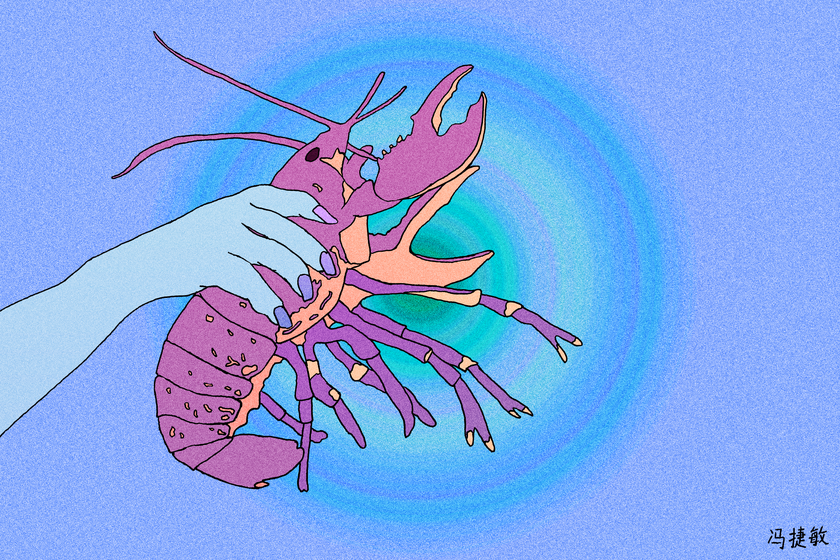

{shortcode-21cc3534b02e5a90dd1b6e61be0fe28423896a7e}t the end of 2021, a year in which I had seen Jeff Bezos go to space, broken up with my partner of 18 months, witnessed mass preventable death on an unfathomable scale, learned the name of the blooming dysthymic revulsion that I had felt toward my body for years but never quite pinned down, destroyed my car during an Instacart delivery, and started wearing makeup, the thing that finally broke me was a YouTube video of a guy who bought a lobster from one of those live lobster tanks at the supermarket and, instead of eating it, nursed it back to health.

He named the lobster Leon. “Later,” he said, “if I find out it’s female, I’ll call it Leona.” I was watching from the floor of my childhood bedroom. Leon’s claw muscles had atrophied from being rubber-banded together, so the guy did physical therapy with him, prodding each claw with a suction tube and gradually introducing foods that required greater dexterity to eat, from worms to live clams.

After two weeks, Leon had regained a full range of motion. When he became curious about his surroundings, decorating the tank with pebbles and discarded shells, I started crying and I didn’t stop.

It was the ease with which the guy had done it. How simple it was for him to care for this animal, and even then, how unexpected it was that he would. How it hadn’t occurred to me that something so close to death could be saved. Still, I felt embarrassed and more than a little surprised: that I was losing it over a viral video from YouTube’s default Recommended page, that it had been more than a year since I had cried for real.

***

Not that I hadn’t wanted to. Over the summer, I had been driving with my mom north from Santa Barbara to the Bay Area. That stretch of the 101 is mostly beautiful, except for the section between San Luis Obispo and Salinas, where it drifts away from the coast and into a lot of needlegrass and construction work.

This was where we were when my mom, whom I love deeply, said, “Are you still depressed?” Cool. It was a question she would spring sometimes, out of nowhere, since she knew I had been depressed but not specifically why.

I said I felt fine.

She said, “Do you want to try using the app they give me through work?” The app was one of the dozen lookalike meditation-slash-journaling hubs that had blown up during the pandemic.

I said I would be interested in trying it. I didn’t realize that she meant right now until she tapped something and a man’s voice started coming from the car speaker.

The voice announced that we were going to begin the meditation session. I glanced at my mom, then, since I was still driving, back at the road: rows of farmland and a few billboards hawking cough drops. The Adopt-A-Highway sign was dedicated to a local prison warden. The mist from the irrigation lines hovered like a cloud layer.

“Slowly close your eyes,” the man said, “and start to focus on your breathing.” I was going 20 miles over the speed limit. My nails were painted this dark purplish blue and it looked like I had bruised them. I tried to focus on my breathing. We flew past a dead raccoon that had been crushed against the median, then another. I kept seeing more, and I wondered if Soledad’s animal population was having a particularly rough day, or if it had always been this bad and I had just never noticed.

The man said, “Now imagine a light moving down your body, starting at the top of your head.” I made a cursory attempt, following the light from eyes to nose to mouth, but I stopped when I got to my jawline. There was something stuck there, maybe myself, and I didn’t have the space to figure out what to do about it. I looked at my mom again.

***

That was also the year I destroyed and rebuilt my understanding of myself. It was an act of expansion: broadening my horizons, my hips, my relationship to grief. For one thing, I have never cried much, and I used to see this restraint as a protective mechanism. I liked that when bad things happened, I could handle them with a level head. But in the course of my expansion, I lost interest in the kind of protection that analgesia offered.

So Leon was cleaning the algae from his tank and I was bawling like the world’s most jaded baby and I was remembering driving with my mom and other moments, dozens of them, where I had needed to cry and found myself unable to.

The inability to physically pass was one thing. While the inability to cry was also a problem of personal autonomy, running into it over and over felt almost worse, because it seemed like it should have been surmountable. I was looking for catharsis. I dreamed of no longer having a body, but I would settle for having mine do what I wanted, and, crying in my room, I couldn’t tell if what had happened was progress or just the bursting of a dam.

Coming to college has not really answered this question, but it has deepened my understanding of a related one, which is why the lobster video had the effect on me that it did. There’s this tendency here to commodify gender into its constituent parts, to latch onto and elevate different markers of identity in a way that feels self-interested, more taxonomical than anything. Even when this tendency is compassionate, it can seem reductive, since the markers never add up to the big picture. I am hesitant to linger on pronouns or trichotomy or the shape of my throat when what I really want is for someone to lift me up out of the supermarket tank and take me home. Teach me to cry or bury me in saltwater deep enough to approximate it.

***

The lobster guy’s name is Brady. He’s still posting video updates, and I check on the two of them occasionally, like an older sibling or a clingy ex. Leon has moved to a bigger tank, fought through illness, played games to test his intelligence. As of March, he has larger claws and a shell free of rubber-band scars: At some point in the interim period, he had molted.

— Magazine writer Bea Wall-Feng can be reached at bea.wall-feng@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @wallfeng.