{shortcode-4b34cdc9720f382de9bb00fb809b96a058840172}

The Period Game, a board game designed to teach menstruation, is simple. You choose your game piece — a pad, a tampon, or perhaps a cup — and spin a centerpiece shaped like ovaries until it drops a marble, color-coordinated to indicate your next move. In this game, getting your period is one of the best things that can happen. It means you get to jump to the next period square on the gameboard, skipping any spaces in between. In fact, you win the game by being the first player to make it around the gameboard to your eighth bleed.

Winning by getting your period is a funny representation of the message behind the larger exhibit that stands beyond the board game table. "Out for Blood: Feminine Hygiene to Menstrual Equity,” the latest show in the Lia and William Poorvu Gallery at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, showcases decades of pamphlets, products, and advertisements related to menstruation.

“We wanted to just have people explore the stereotypes that all these companies had sold to women since 1921,” says curator Lee A. Sullivan, Schlesinger’s head of published and printed materials.

The exhibition is chronological, tracking the history of menstruation in public conversation. The words “sanitary” and “hygiene” recur frequently on the items displayed — as if menstruation is something unclean that needs to be addressed.

Early in the 20th century, this narrative and a lack of convenient menstrual products prevented menstruators from being able to work or exercise during their period. Things started to change in the 1940s, when innovative menstrual products offered people the ability to participate in their lives during the bleed without leakage.

{shortcode-21cd789937215c4332432f3855c8d6bd484e9c4a}

But the popularity of these products advanced a new narrative: that menstruators should not leak. “Throughout the 20th century,” the exhibition’s website explains, “the marketing and design of menstrual products often stigmatized menstruation as an unmentionable bodily affliction.” For menstruators living under this stigma, pad and tampon brands guaranteed the possibility of not being “found out.” Sullivan points to an old box of tampons with the brand “Fibs” written across the front. “It’s like you’re fibbing — that you’re pretending you don’t have your period,” she says.

Moreover, the companies marketing these menstrual products faced little to no regulation. They generated pamphlets that positioned themselves as medical or medically approved experts in menstrual health, then proceeded to recommend their own products. Restrictions were only introduced after multiple product-liability lawsuits established a link between excessively absorbent tampons and an increased risk of developing toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal bacterial infection.

An ad for Nan Robertson’s 1982 Pulitzer prize-winning article on toxic shock syndrome, framed above a photo of her limp hand, ravaged by TSS-induced gangrene, marks a point in the exhibit where the voices of companies are replaced by the voices of menstruators. While the show’s “Prologue” highlights how shame was ingrained in the dialogue surrounding menstruation, the main portion of the exhibition is centered around the long history of activism — and frustration — around changing this public narrative.

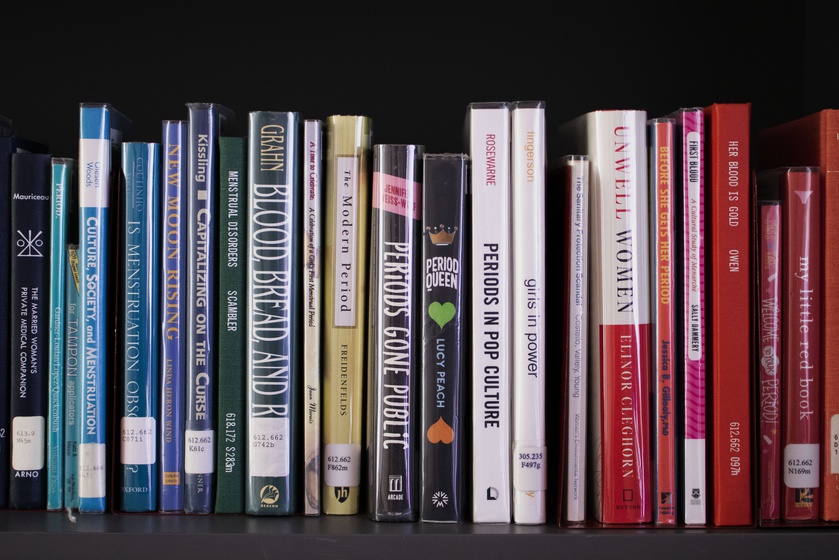

The exhibition pulls a powerful collection of work from the archives, ranging from the diary entries of a young girl to the canonical “Our Bodies, Ourselves” by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collection. From zines to essays to poetry, its message remains decisive. Menstruation, Sullivan says, is “not some kind of ailment, but it’s just a part of your life. It’s a healthy, wonderful thing.” The exhibit is all about menstrual equity – the mission to destigmatize menstruation and make safe menstrual products available to all people.

{shortcode-602674a640c42eb57950ad9f5e69c81ce52487f4}

Alongside the historical objects, an alcove at the back of the gallery displays posters of the 2019 bill H.R. 1882, which would increase access to free period products, and organizations that work toward menstrual equity, such as Love Your Menses.

Visitors are encouraged to bring menstrual products to donate to Love Your Menses. The exhibit also gives information for ways to get involved in menstrual equity organizing in greater Boston.

Chris Bobel, a Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston, also proposes an everyday type of activism. As a moderator for the panel that kicked off the exhibit on Monday, Bobel was asked what visitors could do for the menstrual equity movement after leaving the exhibit. She replied, “At once the simplest and the hardest is to change the way we talk about menstruation. You know, really try to root out the euphemisms from your vocabulary, try not to whisper about this natural body process.”

“Every time we speak menstruation’s name, every time we speak our truth, we speak our experience, we undo what I call the ‘menstrual mandate’ of shame, silence and secrecy,” Bobel said. And at “Out for Blood,” menstruation’s name is said loud and clear.

— Magazine writer Francesca J. Barr can be reached at francesca.barr@thecrimson.com

— Magazine writer Jem K. Williams can be reached at jem.williams@thecrimson.com