{shortcode-f247b59afa37ed0843cbfb007f2a1c0f4396bbb9}

Content warning: This article contains detailed descriptions of physical violence perpetrated against Black individuals.

Tamara K. Lanier picked up the phone mid-conversation. She was talking to a voice on the other line about an upcoming hearing on H.R. 40, a bill which, if passed, would introduce a commission to “study and consider” reparations for American slavery.

Two days later, on Feb. 17, Lanier spoke before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties. She presented her testimony alongside her attorney, Benjamin L. Crump — the distinguished civil rights lawyer representing the families of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor in their civil suits. Lanier’s testimony outlined the decade-long battle she has waged with Harvard over the legal ownership of daguerreotypes picturing her ancestor, Renty.

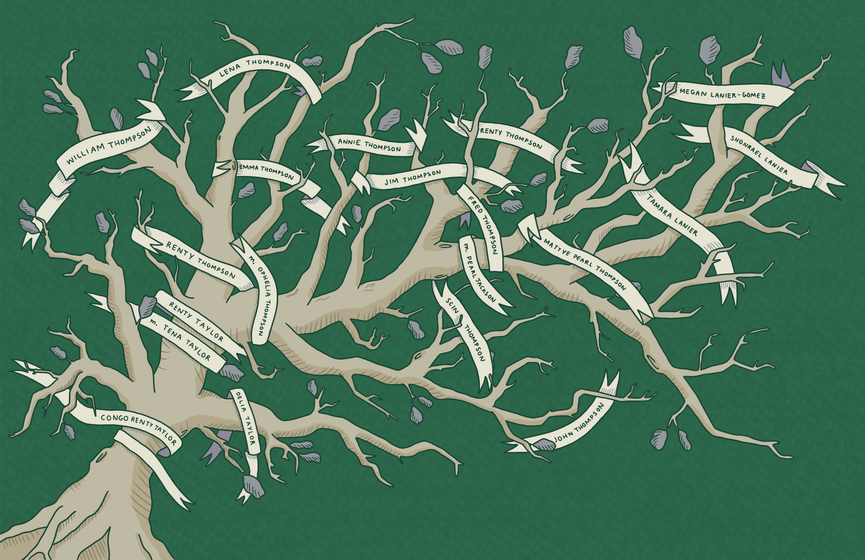

“In our family, there are five generations of Renty,” Lanier says. From childhood through adulthood, Lanier’s mother shared stories of Papa Renty, Lanier’s great-great-great-grandfather who was enslaved in South Carolina. It was her mother’s dying wish for Lanier to research and record her family tree — a feat that is often impossible for the descendants of those who were enslaved in America. “I started to feel the guilt and remorse about promising her that I would write this down,” Lanier says.

Ultimately, she was able to live up to her promise. She did what many other Black Americans are unable to do: identify the plantation where her ancestors were enslaved, speak to the descendants of the owners of that plantation, and verify the family lore that she had heard since childhood with a genealogist.

Near the beginning of her search, Lanier stumbled upon an unexpected finding — photographs of Papa Renty and his daughter, Delia, in the archive of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Her reaction, Lanier recalls, was immediate: “I saw in him family resemblance. The stories seemed to all come to life again when looking at that picture.”

For the past 10 years, Lanier has wrestled with Harvard for ownership of the photographs. Some have disputed whether her genealogical research is 100 percent certain, and The University has said it seeks to “steward” the fragile objects — which are some of the earliest photographs of enslaved people — and make the images publicly accessible. In an attempt to resolve this dispute, Lanier sued Harvard in March 2019 for ownership of the daguerreotypes.

In Oct. 2020, Lanier and her legal team argued their case in front of Massachusetts Superior Court Justice Camille F. Sarrouf, Jr., responding to Harvard’s motion to dismiss the case. The University argued that Lanier has no standing to sue for the photographs because her request exceeds the statute of limitations and because they say she has no legal claim to ownership over the photographs. Earlier this month, Sarrouf ruled in Harvard’s favor and dismissed Lanier’s claim. Lanier and her team have 30 days to submit an appeal, and they plan to do so.

The implications of Lanier v. Harvard do not end with the daguerreotypes in the Peabody Museum. Crump believes that this case could dictate the future of reparations in the United States, saying, “Like Brown v. Board set a precedent, it will set a precedent now.”

“This will become a legal mandate for all of those Black people,” Crump says, “to be able to recover whatever artifacts, relics, artwork — anything of significance or value that was seized from them during slavery.” Such a precedent would bring rising calls for racial justice across America into museums, questioning the very possibility of ethical stewardship.

In January, University President Lawrence S. Bacow announced that the Peabody Museum holds the remains of at least 15 people of African descent who were likely enslaved. Lanier v. Harvard also raises questions over the legal and moral basis for Harvard’s ownership of these remains, as well as the thousands of uncatalogued artifacts that sit in the Peabody.

‘Papa Renty Looks Mad’

“This begins with not only my childhood, but my mother’s childhood,” Lanier says. “She would refer to it as growing up in the Jim Crow South. She was the daughter of sharecropper parents.” Lanier’s mother, Mattye Pearl Thompson, shared stories about Papa Renty that had been passed down through the generations.

Lanier’s daughter, Shonrael P.G. Lanier, vividly remembers these stories as well. “The way that some people do with ‘Berenstain Bears,’ those were the stories of my childhood,” she recalls. “We learned about how hard he worked and how he put that work ethic into his children, and how they went from slaves to sharecroppers to teachers and nurses. Our grandmother was always very proud, and telling us those stories and keeping us grounded.”

{shortcode-7fd08bce8037f7e4e8484e3bd9678bab1f784260}

Both Tamara and Shonrael Lanier remember the story Mattye Pearl told most often: Papa Renty acquiring a Webster’s Blue Back Speller and teaching first himself, and then others, to read, even though it was illegal.

For Tamara Lanier, Renty’s desire to read and teach other enslaved people was “not just physically emancipating themselves from bondage, but intellectually. That part of our story about Renty’s literacy is so, so very important to the discussions and the issues that I’ve had with Harvard.”

The University received the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia with a different backstory — one that Harvard biologist Louis Agassiz narrated. In March of 1850, Agassiz commissioned Joseph Zealy to photograph enslaved people for medical research justified by racist pseudoscience. Agassiz was an adherent of Polygenism — a false scientific ideology that argues that different races come from different origins — and he sought out enslaved people in the American South to study as “pure” Africans.

“Renty had to strip naked. And have his features, his lips, his arms, chest, his male organs, buttocks, everything measured to prove some racist beliefs,” Crump says. “Delia even had it worse in some ways. This young woman standing there in front of all those strange men groping on her breasts and measuring her buttocks.”

Agassiz violated Renty and Delia with the intent to prove that the Black race was inferior to the white race, “and they just had to stand there,” Crump says. Agassiz ultimately gifted his supposed evidence to Harvard.

In her continued efforts to fulfill her mother’s wish of documenting her family history, Lanier was able to identify the man in the daguerreotype as her Papa Renty. She traced her ancestry through old family names that had been passed down through the generations. She then cross-referenced her own research with a genealogist and compared the records and stories she had accrued from the descendents of the family who enslaved Renty.

Lanier says the Peabody Museum initially turned away her genealogical research. The museum’s director of external relations at the time, Pamela Gerardi, told the Norwich Bulletin in 2014 that Lanier gave the Peabody “nothing that directly connects her ancestor to the person in our photograph.” After finding no interest in her research at the Peabody, Lanier says she reached out to then-University President Drew G. Faust saying, “I’m confused.”

“I sent a letter to her that basically gave her a little of the backstory, and I told her that I believe that I am this man’s [descendant], and that I would want someone from Harvard to look at my research and confirm,” she says. Lanier alleges that Faust was repeatedly dismissive of her. Lanier was confused why Harvard, an institution whose very motto proclaims its commitment to history and truth, would be so uninterested in hearing her story.

Harvard spokesperson Rachael Dane, on behalf of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and the Peabody, wrote in an emailed statement, “These highly sensitive objects foreground the dignity and humanity of enslaved Black American and African born men and women, who were photographed against their will. We are hopeful the Court’s ruling will allow Harvard to explore an appropriate home for the daguerreotypes moving forward that allows them to be more accessible to a broader segment of the public and to tell the stories of the enslaved people that they depict.”

Dane declined to comment on behalf of Faust, pointing instead to the University’s statement on the recent ruling in Lanier’s lawsuit.

Lanier’s story flew under the radar for several years as she was directed to different University administrators for answers to her questions. However, things changed in 2017 when she attended a Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study event with her daughter. She walked into the room and immediately recognized the huge image of Renty staring at her. Lanier remembers, “My daughter and I both stopped in our tracks, and I’ll never forget her words. She said, ‘Mom, Papa Renty looks mad.’”

The Laniers took seats in the back. Already offended by the unceremonious display of Renty, the rest of the conference continued to disturb them. Although Lanier had already spent years trying to tell Harvard she knew who Renty was, she remembers the speakers claiming he was “invisible.”

Shonrael started tweeting. She noticed the speakers were telling audience members to respond to the conference with a hashtag, so she started sharing all the research her mother had collected over the years using that hashtag. She says she was attempting to “put out as much information, just trying to beat the false narrative by spreading the truth.” The Twitter thread quickly gained traction, and audience members even started engaging with them. “And that’s kind of how we grassrooted some true information about my grandfather at a conference that was parading his image around,” Shonrael says.

The Radcliffe Institute did not directly respond to the Laniers’ criticisms in multiple requests for comment, but did point to videos of the event, “Universities and Slavery: Bound by History,” publicly available on their website.

After months of organizing and filing a lawsuit against Harvard, Lanier’s story became national news with a New York Times profile. The battle against Harvard’s stewardship of the photographs — one that, Lanier says, centers Agassiz in the narrative and perpetuates his scientific racism by erasing Renty — became mainstream.

Marian S. Moore, the great-great-great granddaughter of Louis Agassiz, grew up hearing stories about how her ancestor discovered that glaciers move. It wasn’t until the Times profile that Moore understood the true implications and racist legacy of Agassiz. After reading the article, she felt compelled to Facebook message Lanier. Ultimately, 43 descendants of Agassiz penned a letter to Harvard imploring the University to hand over the daguerreotypes to Lanier.

Moore says the overarching message of the letter was, “We ignored this for way too long. And now we see how wrong that was. And what we’d like to do is come on this side of the table with Tammy. And can you [Harvard] come over to this side of the table, too?”

“We have the possibility,” Moore says, “and Tammy and I have talked about this, of ancestral healing.”

‘African Americans Have Cultural Property’

There is no legal mandate requiring anthropological museums, like the Peabody, to return artifacts relating to American slavery to the descendants of the enslaved.

By contrast, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, requires institutions to return Native American remains and burial items that have an identifiable cultural or geographic affiliation to their original owners and descendents. The Association of American Indian Affairs recently penned a letter to the University alleging that Harvard is in violation of NAGPRA. The letter accuses Harvard of failing to consult Native American tribal nations during collection inventories, as well as the mishandling of other artifacts.

The Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016 (HEAR), extends the statute of limitations for descendents of Jewish people whose possessions were stolen by the Nazis during the Holocaust, providing descendents the opportunity to sue for their ancestors’ belongings if they can prove ownership.

No legal equivalent has been enacted for remains of or possessions that were taken from enslaved Black Americans.

{shortcode-ee46bb5a36713f03254ef1979a2f318ee6174295}

The Peabody Museum’s Faculty Executive Committee was organized in 2019 to assess and evaluate the museum’s stewardship practices and relationships with descendent stakeholders of their collection. Professor Matthew J. Liebmann chairs the committee and studies North American archaeology and American colonialism.

In Bacow’s announcement of the discovery of the human remains that belonged to people of African descent who were likely enslaved, he also announced the formation of a steering committee to survey and recommend policies on “the ethical stewardship of human remains in the University’s museum collections.”

Liebmann says, “President Bacow’s announcement was so significant because there’s no law that’s mandating Harvard to” repatriate, bury, or study the remains of enslaved people in the Peabody. Similarly, Harvard is not currently required to return the daguerreotypes in question to Lanier — a fact the March 1 court decision allowing Harvard’s motion to dismiss relied on.

Despite the lack of legal obligation, “lots of museums are taking a step back and examining their previous collecting practices, their current guidelines around stewardship, and their obligations to society at large,” Liebmann says. The Peabody’s internal review process helped lead to the discovery that its collections hold remains of individuals who were likely enslaved.

A Peabody panel earlier this month on how museums can decolonize themselves explicitly discussed repatriation of Native American artifacts. There was a similar panel last November. Bacow has also requested the recently-formed steering committee on human remains release a public update on its activities in the fall.

Throughout all of this discussion, Harvard has continued to maintains it has a rightful claim to the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia.

“African Americans have cultural property,” Lanier says, “There’s cultural property that is in museums and the narratives are completely told from the perspective of those who have exploited.”

Crump adds, “And that’s where Ms. Lanier and us African Americans, as descendants of African slaves, are saying, ‘Why aren’t you doing a HEAR Act for us?’”

The Precedent at Stake

Crump thinks that Lanier v. Harvard is the most significant case for racial justice since Brown v. Board.

“We have to remember that Brown v. Board of Education was transcending,” he explains, “because it allowed generations upon generations of people who have been marginalized and denied basic opportunity and equal justice as it relates to what the Constitution guaranteed all its citizens: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Crump believes Lanier’s case would lead to a very similar outcome: “This landmark case against Harvard would be the first case of reparations for an African American family to recover anything from slavery from an American institution.”

{shortcode-e203304844de827d4e279973bf61187b9e44c30a}

The legal basis of Crump’s argument revolves around three central pillars, none of which were central to the March 1 ruling by the Massachusetts State Superior Court. Rather, the court allowed Harvard’s motion to dismiss the case on the grounds that the statute of limitations had passed and that Lanier did “not have a property interest in the photographs.”

Crump’s first legal argument involves equitable restitution. Crump believes that Harvard has acquired unjust enrichment through its use of the daguerreotypes because Harvard has profited off of the violation of Renty and Delia. For instance, in 2017 Renty’s image was put on the cover of a $40 textbook distributed by the Harvard University Press. Bacow has said the University does not profit from the images and only charges a “nominal fee” for reproductions.

For equitable restitution to be applied, there must be a form of unjust enrichment, meaning that profit was made from a crime. “Because of the nature of the pictures’ creation, the images were taken under duress,” Crump says. “This was not just simple duress — this was the most extreme of duress.” He believes that given the severe circumstances, consent could not have been given to the photographer, meaning equitable restitution is applicable.

“If they challenged their slave masters and refused to obey their masters’ will,” Crump adds, “What would have happened to Renty and Delia? They would have been beaten, they would have been starved, they would have been tortured to death. Put simply, it is clear beyond any doubt that Renty and Delia would have never been given any option to refuse to take these photographs.”

The court ruled that regardless of whether or not the photographs were taken under duress, Renty and Delia never had any legal claim to them. The ruling cited several state and federal precedents establishing that “any photographs are the property of the photographer.” Thus, as a descendant of the photographs’ subjects, Lanier has no claim to them.

The second pillar of Crump’s argument hinges on a constitutional law claim. He explains that “by refusing to relinquish the images to Ms. Lanier, Harvard continues to unconstitutionally deprive Ms. Lanier of her rightful property.”

In addition, Crump claims that the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act allows Lanier to sue to get the daguerreotypes back, because by accepting the images from Agassiz and keeping them, Harvard promoted slavery after its abolition in Massachusetts, thus violating the act. “Slavery in Massachusetts ended in 1783. And these daguerreotypes were produced in March of 1850. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865,” Crump explains. “We believed that we were free, that we had the right to our own person, our own image, but Harvard said, ‘No Renty, no Delia. You do not have the right to your images.’”

The court dismissed this argument due to the three-year statute of limitations embedded in the Massachusetts Civil Rights Act. Furthermore, Sarrouf wrote, the bill states that “a person can assert a civil rights claim ‘only in his own name’” and that Lanier herself lacks a “plausible claim for relief.”

The final premise Crump uses is a ‘prima facie’ tort claim, in short, alleging that one party intentionally caused loss to another without justification. Crump asks, “So did Harvard commit these crimes against Renty and Delia with a malicious purpose? We all know they did.”

“They were engaged in scientific racism to advance the cause of white supremacy,” Crump says, “and reinforced racist notions of Black inferiority as a way to perpetuate the institution of slavery.”

Again, the court dismissed this argument due to Lanier’s lack of property standing.

Crump alleges that Harvard’s defense “relies on technicalities.” In the October hearing, Crump pleaded with the court “not to participate in Harvard’s enterprise of profiting from crimes against humanity.” The suit has yet to reach trial phase, meaning that no one other than Sarrouf has heard each side's exact argument. “Let them prove it to a jury of our peers,” he says, so that Harvard can prove “that they should be unjustly enriched by their participation in white supremacy.”

In an interview after the court decision was released, Lanier says that she and her legal team anticipated the dismissal since the October hearing. “There was very little confidence that the judge would rule in our favor,” she explains. “We had at that point talked about plans for moving forward in the event of something like this.”

“There will definitely be an appeal,” she adds. “That is for certain.”

Although she expected the decision, she was still disappointed. She felt as if the court disregarded her main arguments and acted as “a repetition of Harvard’s complaint.”

She had long been under the impression that this case was destined for a higher court. “The question is,” she says, “How high a court?”

Joshua D. Koskoff, another one of Lanier’s attorneys, says, “What we’re going to be doing is filing an appeal. We will try to get this case directly up to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, where it has always belonged, in my view.”

“Current legal principles” were used by Sarrouf to deny Lanier property standing in the case — legal precedents that themselves derive from the very legal system that denies that descendants of enslaved Black Americans have cultural property. Sarrouf wrote that “the Legislature or Massachusetts Appellate Court” would be better suited to “provide the redress Lanier now seeks.”

If they win the appeal, Crump says that this precedent would have tangible outcomes on the descendents of enslaved people living today. “If Black people can prove their lineal descendancy,” he explains, “they can have a legal claim as to what was seized from them or wrongfully taken from them as a consequence of slavery.”

Nonetheless, Crump does not think such a precedent would lead to an overwhelming number of individuals using the court to acquire property they believe was stolen from their ancestors. “I don’t think there will be a floodgate,” he says. “Because we’ve got to remember, slavery was designed to make sure Black people can never trace their roots.”

Lanier and Crump have already used their unique position and the importance of the suit to push for reparations outside of the judiciary. On Feb. 17 the pair testified before Congress during the hearing on H.R. 40, calling for a commission that studies reparations for American slavery.

Lanier says that their statement to Congress was “not only [about] reparations, but decolonization, repatriation, sexual exploitation, cultural appropriation. This is what this case represents — all of these things in one, and then beyond that.”

Is There an Ethical Steward?

During Lanier’s legal endeavors, grassroots organizers and activists have rallied behind her. Samantha C. W. O’Sullivan ’22, the president of the Harvard Generational African American Students Association (GAASA), has played a key role in student activism around the daguerreotypes. After GAASA hosted a few panels with both Lanier and Crump to raise awareness about the lawsuit, a student wing of the Harvard Coalition to Free Renty was born. The activist organization has hosted meetings as a platform for Lanier to appeal to the Harvard student body and has circulated petitions demanding the Peabody release the images.

Although O’Sullivan has been a key organizer in this grassroots campaign, she remains pessimistic. “We would hope they would return them, but I don’t see them doing it,” she says.

She feels that Harvard’s actions toward Lanier send a larger message to Harvard’s Black student body. “It feels very hurtful and very alienating in the sense that it’s almost like the College is telling me, as a Black student descended from enslaved people, that ‘we don’t care about your ancestry,’” she says.

Despite O’Sullivan’s admitted cynicism, she still believes that “the most that any of us can do as students is to use our voices.”

A number of Harvard institutions are attempting to reckon with the racist scholarship conducted in their past. Liebmann says the Faculty Executive Committee of the Peabody, for instance, is working to create policy recommendations to “prioritize ethical stewardship as part of the fundamental mission of the museum.” He adds that the committee is most recently focused on “how we can use the Harvard collections to reflect on Harvard’s history.”

In a 2019 email to the Faculty Executive Committee of the Peabody Museum, Jane Pickering, the museum’s director, wrote, “Ms. Lanier’s complaint raises important questions regarding, among other things, what it means for the Peabody to serve as an ethical steward of highly sensitive objects like the Zealy daguerreotypes.” That year, Pickering wrote in a statement to The Crimson that the Peabody aims to make the images publicly accessible “to tell the stories of the enslaved people that they depict.”

Crump, however, dismisses such claims of ethical stewardship. “One hundred sixty-nine years later, Harvard is telling Ms. Lanier and all the world that ‘No, Black people, you still don’t have the right to your own person,’” he says.

“You’re going to let the wrongdoers, the people who were perpetuating racism, now come and teach the world about racism?” Crump believes that Harvard is “not in a better position to be able to educate us on racism, especially when [Harvard was] so engaged in it for so long.”

When asked what she would do with the daguerreotypes if she gains ownership of them, Lanier says, “I just don’t want Harvard to have them, because they have never been the ethical stewards of these images.” On the contrary, Lanier likes to refer to Harvard as “the unethical stewards” of the images “because for the last 10 or 11 years of my journey, and my battle with Harvard, they lied every step of the way.”

“What I plan to do with them is secondary to having the right to decide what to do,” Lanier says. “The issue is: Why does Harvard have them?”

— Magazine writer Maya H. McDougall can be reached at maya.mcdougall@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @mayahmcdougall.

— Magazine writer Garrett W. O’Brien can be reached at garrett.o’brien@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @GarrettObrien17.