{shortcode-103a2f2607fbb08f0c6fd7a4896b66e4dbe3abd6}

Content warning: This essay contains descriptions of disordered eating, calorie counting, suicidal thoughts, and related behaviors.

If you scroll deep down through the Notes app on my phone, you’ll find a document titled “Food Tracker.”

It begins July 1, 2020. Breakfast: overnight oats (400 calories). Lunch: toast (130), ½ avocado (90), olive oil (25). And it continues like that for days and weeks, a meticulous mathematical inventory of everything I had consumed.

Even though I was a humanities student, it felt like I was doing three psets a day.

I started dieting in January 2019. I didn’t even know I was dieting at the time. All I knew was that many of the girls at my high school were skinnier, prettier, and cooler than me. Prom was in five months, and I wanted to look like them in my pictures. I bought a dress a size too small to motivate me toward my goal.

So I stopped eating rice, bread, and fried foods. I increased my vegetable intake and began working out every day. When people asked me about my new food and exercise choices, I called it a “lifestyle change” or “being healthier.” I said I felt “cleaner” and “more energized.”

Whatever coded language I used did not change the fact that I was cutting out entire food groups to starve myself into a smaller body.

It worked, at first. As I weighed myself each week, I saw the number on the scale get lower and lower. I got compliments from family members and friends. My prom dress fit me perfectly, maybe even a little too big. I felt confident. Beautiful. Loved. Sure, there were days when I lost control and ate an entire bag of Dove dark chocolates. But then I would cut back, and everything was fine again.

And then came quarantine. Fearing I would gain weight at home, I became even more militant with my dieting. I started running four to six miles a day. I refused to eat my dad’s home-cooked fried rice, a dish that used to be my favorite.

After dinner, however, I would check to make sure no one was around, open the pantry, and eat whatever I could get my hands on. I started thinking about food from the moment I woke up until the moment I went to bed, my brain constantly juggling numbers and ingredients and feelings of self-loathing. You might call my behavior “disordered.”

In August 2020, just two weeks before beginning my sophomore year of college online, I called CAMHS and asked to make an appointment with a therapist. I didn’t consider my problem to be particularly serious, but I wanted to be proactive with my mental health. I assumed I would only meet with a therapist a few times and get everything straightened out.

It turns out that sticking with recovery has required more willpower and strength than dieting ever did.

***

In most eating disorder treatment plans, the first step is learning to eat normal amounts of food again. My therapist put me in touch with a Harvard dietician. At our first meeting, my dietician asked me about my typical meal schedule. When she found out that I refused to eat carbohydrates except for oatmeal, she gave me homework: eat starches at every meal.

What had made me such a good dieter was that I was persistent and great at following rules. I applied the same diligence to recovery. I began eating rice and quinoa and bread. The improvements were astounding. Suddenly, my energy levels skyrocketed. I no longer felt cold all the time. I even started trying “challenge foods” like cookies, chocolate, and granola.

The honeymoon phase didn’t last long.

When I first began recovery, my biggest question was, “But will I gain weight?” For two years, I had fought tooth and nail to become smaller. And in my head, smaller meant prettier, cooler, better in every way. I didn’t want to let all my hard work go to waste.

My dietician said that my body could change during recovery, but I wouldn’t know unless I tried. And as the people-pleasing patient I was, I did everything I was supposed to do, from eating dessert to skipping workouts.

Naturally, I gained weight. Looking back, this is obvious — I had been basically starving myself and was now finally getting appropriate nutrition. But at the time, it felt like a slap in the face.

I felt self-conscious about everything. The waistband of my jeans fit tighter than it used to. My favorite boots no longer zipped all the way up my calf. I couldn’t pay attention in class because I kept staring at myself in the Zoom camera, wondering where the sharp angles of my face had gone.

I felt like I had failed. All my life, I believed that I could do anything if I just put my mind to it. But I had tried to lose weight, and in the end, my body couldn’t handle it. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t be beautiful or popular or worthy of love.

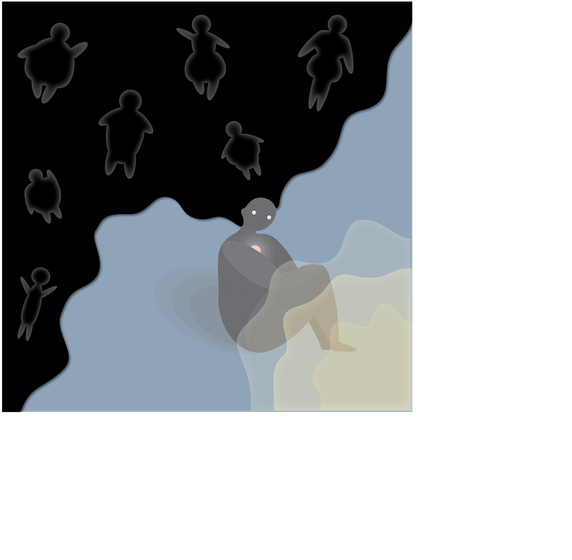

There were days when I couldn’t bring myself to look in the mirror. There were days when I just laid on my bed and cried. And there were days, darker days, when I simply felt tired of living. If it hurt this much to exist in my body, why should I exist at all?

***

I’m not alone in this. When I started talking about my recovery journey on Instagram, an astounding number of people reached out to me and told me about their own struggles with food and body image — people who were so gorgeous and kind and wonderful I had no idea they could ever be insecure.

When so many people are going through the same thing, it’s not a problem with the individual. It’s a problem with the system.

As I started following anti-diet activists, I learned the full extent to which weight stigma pervades our society. Fatphobia is a capitalist construct that fixates people on unattainable goals so they will be forced to buy useless weight loss products forever. In reality, health and happiness can exist at every size. But if everyone understood that, countless white male business owners would be out of a job, so naturally, we must stay in the dark.

Fatphobia is also extremely intersectional, sitting at a crossroads between racism, sexism, and colonialism. As a cisgender female who wears standard sized clothing, I must acknowledge that I still hold a great deal of weight privilege that shelters me from the nastiest acts that our friends in larger bodies face regularly.

For years, films have degraded and desexualized larger women of color to highlight petite, demure, white heroines. Magazines photoshop images of their models to create impossible beauty standards. This is part of our culture, our heritage.

I, like many Harvard students, consider myself committed to breaking down racist, patriarchal, and colonial structures. But by playing into weight stigma — refusing certain foods because “they’re so bad,” watching diet ads aired on New Year’s, posting “before and after” photos on Instagram — we perpetuate the very values we claim to despise.

And that’s not something I want to do anymore.

***

These days, I’m doing better. I am lucky to have a supportive treatment team, a loving family, and good friends. My disordered eating behaviors are under control, and I started working with a clinician outside of CAMHS to fine-tune some of the mental aspects of my recovery. Some days are definitely harder than others, and while I am not fully recovered, I am starting to imagine what a normal life might look like again.

Last night, I ate a scoop of ice cream for dessert. Caramel cookie crunch. A few months ago, I would have shamed myself for hours afterwards or panicked and eaten the entire carton.

But instead, I finished my scoop and went to bed, feeling a pleasantly peculiar sensation of lightness and peace.

— Magazine writer Callia A. Chuang can be reached at callia.chuang@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter at @calliaachuang.