{shortcode-8ddb0770916c4a95e26a2ef65e354cc4fd0aef41}

“I found it.”

“But I saw it first.”

“But I found it.”

“But I saw it first.”

“What about me? I figured out the clue.”

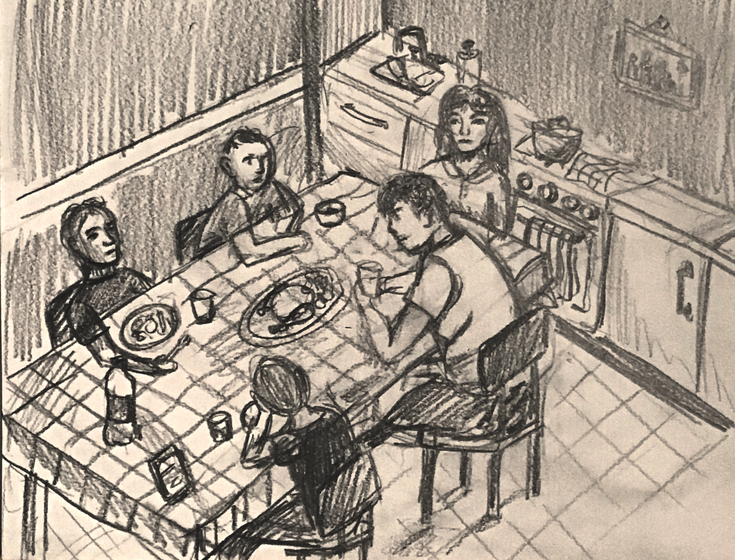

I didn’t actually think that was a valid claim, but it was nice to stir the pot for once, having so many times been the one shoved into the stew. My father yelled to us from the kitchen, diffusing what, in a few minutes, would’ve become a fistfight. We came back to the table to plead our cases for the coveted $10 prize for finding the Afikomen, the ceremonial piece of matzah hidden for us to find each year. My two brothers and I sat, Max and Zack fuming at each other but feigning best behavior to gain credibility as the Seder went on. Next, the tale of the Four Sons — wicked, wise, simple, and meek — which my father likes to tell.

“Our ancestors, being newly freed from slavery, are en route to the promised land, but they are so fed up with their whining kids that they decide to take a break from trekking through the Egyptian desert to record for posterity what made each of them a unique pain in the ass.”

The table erupted, and the yearly tradition ensued: a fond recollection of Max’s wicked deeds of the year, a listing of my latest academic achievements, and — being the catch-all for simple and meek — a reminder that Zack, however old he gets, will always be the baby. For reasons I would only understand later on, each of us is incredibly proud of our ancestral trait.

The meal went on. The fight resolved, as it always did, with Saba Moshe reaching into his wallet to give consolation prizes to the sore losers. For dessert, we shared chocolate matzah and passed around a plate of berries and melons. Moshe, taking a big bite of a watermelon slice, said, “You don’t know how to pick a watermelon. I will show you what a good watermelon is,” suppressing a cough as he spoke by clearing his throat. He and Nanny Rita rehashed their constant argument about his retirement, and wasn’t he too old to be driving Uber still, and did he plan to drive himself to death?

Soon, bellies were full. Young grandchildren were antsy. And old grandchildren bickered. And cousin Talia was drunk. And the rest of the adults were ready for bed. And Glenda complained. And Rita nagged. But no one got up. And Moshe was happy.

He schlepped us to the airport the next day, as he always did, and we flew home. And some weeks later, Moshe, halfway to the door on his way to work, collapsed onto the couch, where Rita found him, struggling to remain upright as he hyperventilated — in and out and in and out. Seconds went by like minutes, minutes like hours. Sirens blared in the distance.

I was in the city visiting my friend Leah that day, trying to circumvent the rising tension at home. Since the lockdown had stripped all semblance of autonomy from our lives, my family resorted to exerting it on one another. Max’s right to sing trumped my right to quiet. My parents’ right to company conceded to Zack’s right to isolation. There were conflicting claims to use the bathroom and equal entitlements to the good spot on the couch, to the last avocado, to host a friend in the backyard. It was suffocating.

I needed the escape, to pretend things were normal. I imagined it was okay to visit a friend, get a coffee, go for a walk. I imagined Leah’s smile under her mask. I imagined my family missed me. I imagined a lot of things.

After I got the call that my grandfather was in the hospital, I spent the drive home crying and worrying for him. No, I didn’t. I was too busy dictating dozens of iterations of a text to Leah to tell her I may have infected her, too worried of whom she might tell, of how I might look, of what might come of my recklessness. I blew past my exit.

At least when I finally got home, my family took the opportunity to come together to hope and pray. Except, we didn’t. We just fought about who had been most irresponsible: What were you even thinking, Sam? Do they not teach common sense at Harvard? How my father had stayed an extra week in Florida and infected us. How he had to quarantine in his room, now — like right now, Dad, get away from us! How we couldn’t leave the house for any reason. How we had to go get tests. How Max had still been out smoking weed with his friends. How Zack was a narc and to hell with you we all bring our own bongs.

We left the kitchen table in tears. We didn’t mention Moshe once.

Exhales, but not his own, even and mechanical, as if from inside a spacesuit as he hurdled alone through the vast expanse of black. Sedated. Intubated. Alone. Only the beeping intervals of his heart monitor for company. At least that’s all we could imagine from the curt, methodical updates the doctors gave my grandmother over the phone, which she relayed to us at home.

But we couldn’t imagine it, not really. We hardly wanted to. We busied ourselves with mindless work and sleepwalking through the hallways of our house, organizing closets we hadn’t used in years, getting on each other’s nerves for no other reason than it was something to do.

When Saba Moshe eventually died, it came as a relief. Yes, it did. We were out of limbo. We could finally grieve, which was something we had learned how to do, had practiced and perfected when Great Grandpa Morris died on New Year’s Day and when Poppy Billy died the summer before that.

But then we remembered we couldn’t go to the funeral. We couldn’t see Nanny Rita. And Aunt Jennifer wanted to delay the burial until she could get a flight from Israel. There were no flights from Israel; there were no flights anywhere. There was no way for us to connect with him, to really know him in the way you only can while sitting around the kitchen table at a shiva. There would be no old friends to meet, no war stories we hadn’t heard before. Well, at least there was Zoom. Meager morsels for starving hearts.

— Staff writer Sam D. Cohen can be reached at sam.cohen@thecrimson.com.