{shortcode-65c6ea50812102243dc63b8c0e80daacb48c44cc}

This wasn’t how I expected to spend my 21st birthday. But it was October, and given the lockdowns, pickings for a venue were slim. I’ve never been good at making decisions, and I certainly wasn’t going to start now — so I searched “restaurants near me” on Google and chose the closest one.

My friends and I loaded into the car and drove off into the night. We got on I-195 and pulled up to our destination.

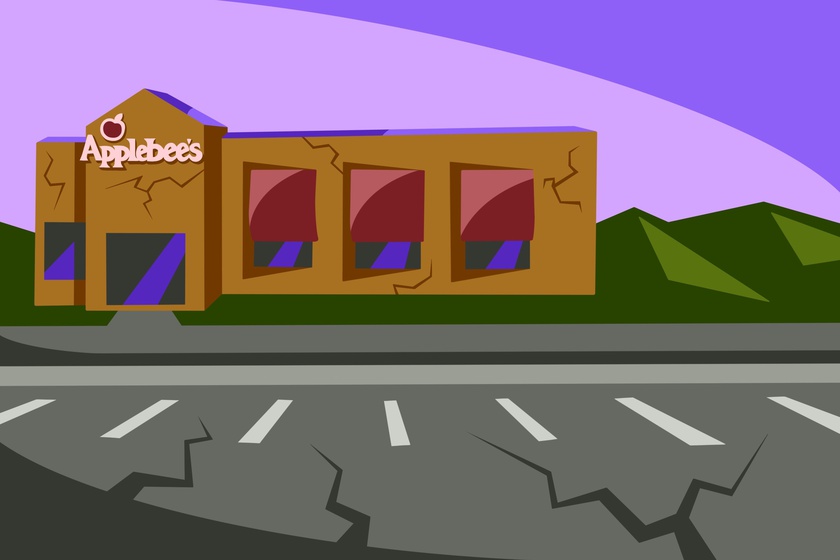

“I didn’t even know this place still existed,” I told my friends as we got out of the car. “All the ones near me have closed.”

“I wonder why,” one of my friends mumbled back, clearly annoyed by Google’s choice.

Masks covering our faces, we entered Applebee’s.

***

Growing up, I trained myself to expect things to be bad so that I’d never be disappointed. At worst, I told myself, I’d have a bad experience, and at best, I’d be pleasantly surprised. But I’d never risk feeling unfulfilled.

I’ve learned over the years that New Year’s Eve is never as fun as I’d like, for example. Rather than hope that I’ll suddenly feel the magic of the ball drop on my TV screen, I’ve come to accept that if I want to enjoy New Year’s, I need to set low expectations. If I end up having fun, then great — but if not, I can just remind myself that Dec. 31 is no different from any other day.

I’ve used this attitude for a lot of things.

But my friends and family would tell me that if I approached experiences with a bad attitude, of course I’d have a bad experience. Deep down, I must have wanted to believe that they were right — so I decided to take their advice in college: I promised myself that things could live up to my expectations if I went in positive. Throughout high school, I convinced myself that college would be the best four years of my life. I was going to be an engineer. I was going to join the band and know all my professors. I told myself that I would, that I should, be able to find friends like the ones I had at home,that being away from home wouldn’t be hard for me.

But by November of freshman fall, I had switched my major twice and stopped playing the saxophone. Not one professor knew my name. I was homesick.

***

The tables looked like they had been stolen from an abandoned Chili’s; if you dared rest your forearms on their dark surface, they stuck to your skin. The light fixture above my head flickered, adding to the restaurant’s Halloween-themed (I think?) decor. My chair was unsteady, and I rocked back and forth trying to flatten the fourth leg on the crusty checkered floor.

“What’s in the Vampire?” I asked the waitress as she stopped by for our drink orders.

“Vampire is bloody delicious with a mix of rum, strawberry, dragon fruit, passion fruit and a dash of pineapple,” she read to me from their $1 monthly specials drink menu. She quickly remembered to smile at the end.

“I’ll try that,” I told her as I proudly handed over my ID.

When she brought over the drink, the first thing I noticed were the plastic fangs floating at the top — they were impossible to miss. It was certainly unique.

I took out the cherry and took my first sip of the mystic purple mixture.

***

“I can’t believe I set myself up like this,” I whispered to my mom on the phone on a particularly rough November night. Despite her best attempt to cheer me up, I curled up in my miniature Wigglesworth room and went to sleep, vowing to keep my expectations low.

And I did just that.

On housing day, my blocking group got Leverett. “Yes! Not the Quad,” I shouted to my blocking group. Their blank faces showed their obviously mixed emotions; Leverett is consistently rated one of the most average houses. I was ecstatic, though — it could have been worse.

The summer after freshman year, I interned in San Francisco. Before going there, I looked up all the city’s faults: high cost of living, shit on the sidewalks, Cali bros. Despite all of the issues I had discovered preemptively, I loved my experience: the aesthetic, the young population, the craziness of downtown San Francisco, the great internship experience outweighed everything I’d worried about.

My sophomore fall, I scored Red Sox tickets for a really good price. Despite being a huge baseball fan, I still assumed something would go wrong: the seats would have an obstructed view, or my favorite player wouldn’t be in the lineup. When the game was postponed due to rain, I wasn’t surprised. My expectations were set low enough that I was fine with the outcome. I learned to be satisfied with mediocrity.

***

“You’ll always remember your 21st birthday,” my uncle used to joke. “Well, maybe not all of it.”

{shortcode-ce816ff6e4eb7015bff6824fe2cccce1192b62d0}

That’s probably why it’s hard to suppress your excitement for the biggest milestones. There’s more than just your own expectations; there’s external pressure associated with them, too.

I had anticipated my 21st birthday for a while, subconsciously telling myself that it had to be epic and unforgettable.

Yet there I was, sitting in a musky Applebee’s in the middle of a pandemic, feeling that this day, like many others in quarantine, would fade into the unconscious part of my brain, the part filled with faded memories, dullened emotions, and forgotten inside jokes.

In that moment, I began to reflect on my mindset toward expectations. I couldn’t shake the feeling that my attitude somehow impacted my experiences. On one hand, my low expectations offered a way out of ever feeling disappointed, but on the other hand, I stopped myself from feeling any preliminary excitement for anything — and that limit on anticipation seemed to somehow limit the experiences themselves.

Maybe it was all of the extra time I had to think in quarantine — or maybe it was that no matter how low my expectations were, the pandemic still found a way to let me down.

As the world adapts to a new normal, we’ve all had to adjust our expectations. For most, the experiences of the pandemic — virtual graduations, cancelled internships, stay-at-home Friday nights — have probably been a lesson in not expecting too much.

And yet I’ve found myself rethinking this mentality, the same one I had for years employed as a defense mechanism. I realized that expectations can be more than just high and low. They can be optimistic, pessimistic, and realistic. They can be definitive and suggestive. They can be open and they can be closed.

Expectations are a constantly changing measure of the future. Low expectations soften a blow, but they are also a form of resignation, restricting what I can feel not just before, but also during, an event.

By only setting high or low expectations, and then treating that measure of the future as definitive, I didn’t just limit disappointment — I limited the surprise and joy that arise when expectations are, well, wrong.

***

I’ll remember my 21st forever, I think.

Maybe it was something about the building, placed perfectly next to a Walgreens and Big Blue Car Wash, the second “p” in the neon Applebee’s sign flickering between bright and dim. Maybe it was the sticky tables, the flickering lights. Or perhaps it was the four of us wobbling our chairs and laughing our heads off as we played Charades on my phone and talked about how ironic it wais that Al Capone’s brother was a Federal Prohibition agent.

{shortcode-ce8eb665111e406f6329f2d321c0d5224431fac4}

I slurped down the first Vampire pretty quickly. It tasted like you’d expect: a pinch of cheap alcohol with some artificial fruit flavors. It was more about the ambience of the $1 drink than the actual taste, anyway. My unattainable expectations for my 21st were fulfilled in a new, maybe even better way.

I started to think about my original advice. Before an event, there is anticipation; afterward, a memory. Anticipation shapes experience, and experience constitutes memory. What will I remember in ten years, and just as importantly, how will I remember it? Do I want to remember the good and the bad, and how will I distinguish them? How can I make peace when things go wrong without missing out on the excitement and hope when things go well?

“Scott, what’re you thinking about?” my friend Sarah asked, noticing my blank face and crooked stare.

“Nothing important,” I said, smiling. At that moment, the waitress came back and asked if we needed anything.

“I’ll have another Vampire, please,” I said. I put the fangs in and handed her my cup.

— Magazine writer Scott P. Mahon can be reached at scott.mahon@thecrimson.com and on Twitter at @scott__mahon. This is one of eight essays published as a part of FM’s 2020 “Synapse” feature, about gaps and how we fill them.