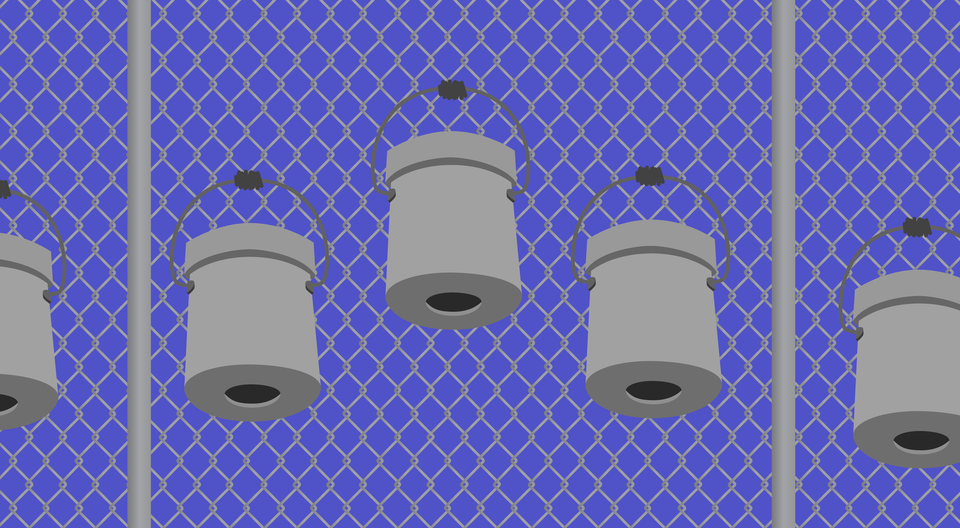

The sun beat down on the back of my neck, as it did every afternoon at Lime Kiln Farm in West Coxsackie, N.Y., but this time I barely noticed it. I was busy helping the farmer, Brent, a stout 50-something with a sharp wit and an affinity for cut-off jorts, hang white paint buckets on the fence behind the farm store. In the bottom of each bucket was a jagged hole about the size of a tennis ball. “That’s where their heads go before we chop ‘em off,” Brent explained to me, swiping his index finger across his neck in a mock-decapitation. Today was chicken slaughtering day.

“And you want to be a part of this?” my mom asked me, incredulous, when I’d told her about it on the phone the night before. She wondered why I, a quasi-vegetarian (or “flexitarian,” the term I like to use), would want to partake in the slaughtering of animals — especially after Brent had emphasized that volunteers were by no means required to attend. I’d come to the farm in the first place to reacquaint myself with the natural world, my mom reminded me, not to actively harm it. But I didn’t need to think twice about the decision. “It would be morally wrong not to,” I declared, preparing to launch into an explanation I’d spent the past few days refining.

The way I saw it, participating was a noble thing to do. I’d decided to go flexitarian a few months back because, for me, the experience of eating meat just wasn’t gratifying enough to outweigh the practice’s ethical and ecological repercussions. But I made occasional omnivorous exceptions (the “flex” moments of my flexitarianism) for meat that had been slaughtered humanely. For chickens, this entails turning the birds upside down and slitting their throats or chopping off their heads — the same method Brent used at Lime Kiln. I figured, if I was comfortable eating chickens slaughtered this way, then I should also be comfortable witnessing, even actively participating in, chickens being slaughtered this way. As I saw it, if sitting out the slaughter would call its humaneness into question, then participating in it should, by contrast, lay such questions to rest.

Early the next morning, we loaded the birds, flapping furiously in our grips, into the back of Brent’s pick-up. By noon, we’d pitched a white tent on the lawn behind the farm store with a gray folding table underneath it to serve as the carcass-cleaning station. Brent and I were stringing up paint buckets when a few friends of his, also farmers in the area, arrived to help out. Introductions were made as we waited for the pot of water next to the tent to heat up. (Dipping the chicken carcasses in boiling water, Brent explained to me, makes them easier to de-feather). When it reached a boil, we got down to business.

Each of us had a role. Brent and Nate were on head-chopping and carcass-dipping duty, Suzy and Alessandro were in the farm store kitchen cleaning and butchering, and I was the link in between the two stations, chopping off feet and plucking any feathers the de-feathering machine had missed. Then I’d deliver the birds, one by one, to Suzy and Alessandro in the kitchen. My foot-chopping technique was less than exemplary — more of a labored hacking-away than a chop — but I was making good time, keeping up my supply with Suzy and Alessandro’s demand. As I handed one of the pink, pallid masses to Alessandro, I thought about the chickens I’d placed in Brent’s truck the day before and wondered which of them this one was.

***

In his essay “Consider the Lobster,” David Foster Wallace wades through the various moral arguments for and against the killing and eating of lobsters, a debate much like those regarding the killing and eating of any other animal. But it differed from chickens, I noted to myself when I read the article a few weeks after leaving the farm, in that the lobsters were boiled alive. Chickens, on the other hand, were long dead by the time they were cooked. This distinction felt both meaningful and comforting.

At the front of our assembly line, Brent and Nate sliced off chicken heads, immediately stepping back when each decapitated body started writhing violently, throwing itself against the inside of its paint bucket. This wasn’t as bad as it looked, I reminded myself, because pain is registered in the brain, and the chicken’s brain was somewhere in the grass about three feet below. Plus, even if I’d wanted to avert my eyes, I’d still be able to hear the body thumping against its container and the metallic clanging sound of the paint bucket bouncing against the wire fence. I figured I might as well just get used to it. “This is what you signed up for,” I thought, yanking a fistful of feathers off a wing.

I didn’t expect the almost-de-feathered chickens Brent slapped onto my table to smell so much like the raw chicken you’d buy in a grocery store, given that I’d seen these bodies clucking and walking around only minutes earlier. The transition from “chicken” to “poultry” was startlingly swift. And it was a transition that, I determined, ended with me: those vaguely prehistoric feet being the last shred of evidence that these pink, fleshy mounds were once living things. My task of separating legs from bodies, severing the last link between sentient creature and agricultural commodity, would have felt kind of poetic if my chopping technique were more refined.

In his essay, Wallace doesn’t attempt to endorse one side on the question of killing and eating lobsters: His project is simply “to work out and articulate some of the troubling questions” that the practice gives rise to. In the end, Wallace concedes that the arguments on both sides are “so totally inconclusive,” that, as a practical matter, it really just comes down to your own conscience — “going with (no pun) your gut.” And, where one person’s gut reaction might be indifference, another might feel troubled by the lobster’s thrashing around and scraping of the kettle, the fact that it “behaves very much like you or I would if we were plunged into boiling water.”

“Ope, we got a runner!” Brent called out. A headless chicken had jerked its way out of its paint bucket. Now it was running — full on, one foot in front of the other, running — in an erratic spiral on the ground, spattering blood all over the grass. Nate and Brent let out shouts of, “Whoop, there she goes!” and, “Got some life left in ‘er!” before the creature finally slumped over in a white and red heap. I wasn’t sure what my facial expression looked like as I watched the scene, but whatever it was, it made Nate go quiet when he turned to look at me. He took off his baseball cap and scratched his head, suddenly self-conscious. “You have to joke about it,” he shrugged, “otherwise it’s just too sad.”

That night, recounting the experience to a friend on the phone, I said I was glad I did it. And I was: I didn’t feel quite as righteous in my decision to eat “humanely” slaughtered meat as I had before, but I did feel a sense of satisfaction with myself for having participated. “Like I’ve atoned for it in some way,” I explained to my friend. “And that feels good. Like, cosmically, some sort of balance has been struck.”

***

Reading Wallace’s essay weeks later, it was hard to ignore the overlap between the lobster-boiling debate and my chicken-slaughtering one. For instance, I was certainly guilty of the same confirmation bias Wallace describes: I mentally assembled a lineup of pro-poultry consumption arguments to deploy as I read — “Decapitation probably doesn’t inflict pain,” “This is how the food chain works, so it has to be morally sound,” etc. But, as troublingly familiar as much of the essay was, even more unsettling was the part that did not feel so familiar, the part I didn’t recognize in my own process of moral inquiry: Wallace’s central question. “Is this practice ethical?”

My rationale for participating, which at first had seemed morally airtight to me — “If I’m fine with this kind of thing happening, then I should be fine with watching it happen,” — glosses right over this question: Am I actually fine with this happening? Should I be? Sure, Lime Kiln’s method might have been the most humane relative to others, but is it actually humane at all? Like Wallace, I didn’t have an answer to this question. And so I’d dodged it altogether.

On some level, I was conscious of this question before I even set foot on our makeshift slaughtering station behind the farm store. I must have had doubts as to whether I could morally reconcile my decision to eat “relatively humanely” slaughtered chicken, or else I wouldn’t have sought out confirmation of this decision in the first place. My moral justification, put another way, was, “If I’m going to be complicit in what is, at worst, the brutal execution of a living thing for the purposes of some momentary, inessential human pleasure, then the least I can do is acknowledge my complicity.” I knew it was possible that I might have been doing something wrong. And, far from assuaging this unease, witnessing the slaughter brought it into even sharper focus.

And yet, I’d still walked away from the experience feeling weirdly good about myself. I’d called up my friend that night talking about “atonement” and “a cosmic balance” that my presence at the slaughter had established. And this self-satisfaction had lasted a while: Weeks had passed, an entire David Foster Wallace essay had been read before I was finally, now, beginning to investigate this mysterious mechanism by which I could feel absolved for something without ever explicitly identifying what it was I was seeking absolution for. The word “atonement” had come to mind the night after the slaughter, and it seems I’d forgotten — maybe not intentionally, but not quite unintentionally either — that you atone for something sinful. But the moral-emotional progression I’d undergone felt like such a natural one: Confront your shortcomings; feel less guilty about them.

This conclusion felt logical and familiar — probably because we all do this. Journalist Katy Waldman even coined a term for the practice: the “reflexivity trap,” which she defines as “the implicit, and sometimes explicit, idea that professing awareness of a fault absolves you of that fault.” The term pretty accurately names what I’d been doing since I left the farm: the “moral work of feeling bad,” as Waldman describes it. What did a chicken care if I acknowledged my complicity in its death? It still died. I still watched it convulse in its death throes. I still watched it tumble to the ground and start running, frantic and headless, speckling the grass with blood before it finally — humanely! — expired. For all the time I’d spent considering the slaughter and consumption of chickens, at no point had I confronted David Foster Wallace’s more discomfiting challenge to “consider the chicken” and reevaluate my dietary choices.

It’s a powerful and versatile instrument, self-awareness — for me, it’s been both a catalyst for self-betterment and a shield against it. But now I think I’m a lot better at telling the difference.

And, for whatever it’s worth — to chickens, or to the cosmos, or to my own self-image — I haven’t bought chicken since June.

— Staff writer Liv R. Weinstein can be reached liv.weinstein@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @livweinstein.