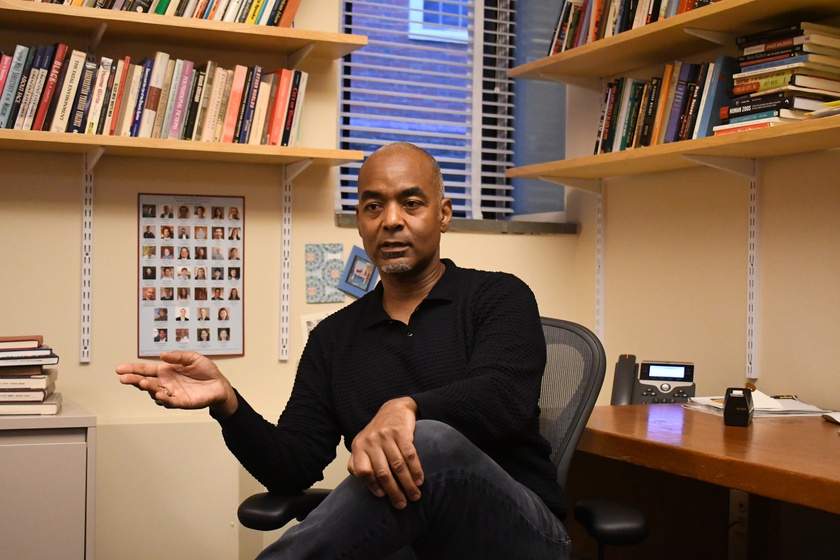

When read a withering criticism lodged in his most recent book, where he describes universities as reproducing a “disembodied universalist white order,” Robert F. Reid-Pharr –– a leading scholar in African-American studies and Harvard’s first tenured professor in the Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality –– smirks.

“I meant it more sweetly!” he insists with a grin.

At the center of Reid-Pharr’s relationship to Harvard lies the following contradiction: a gay, black man from a working-class background who produces uncompromisingly radical scholarship on race, gender, and sexuality at an elite institution that, he says, is “built on the bodies of people of color, women, sexual minorities, working class and poor people.”

And this zeal doesn’t abate when Reid-Pharr leaves campus — he believes human oppression underwrites society. It is as persistently present on his walk to his local Whole Foods as it was during his childhood in North Carolina.

“The question for me,” he says, “is about thriving, regardless.”

In 1987, Reid-Pharr arrived at Yale to pursue a Master’s in African-American Studies, subsequently earning a Ph.D. in American Studies in 1994. When he arrived in New Haven, he had never met somebody who had attended an independent university. His classmates all seemed to be experts on Michel Foucault, and he had no idea who that was. “I didn’t understand the way people dressed and the way that they carried themselves,” he says. “I didn’t understand people’s backgrounds. I just was a fish out of water.” He says he was fortunate to have professors and mentors who recognized his potential and guided him through Yale’s foreign landscape.

The mentorship he received at Yale drives Reid-Pharr’s current teaching philosophy. “I hope that what is attractive to students about me — sometimes, I can be a pain in the butt, too — but I hope it’s that I'm not trying to get people to cut off parts of themselves in order to be around me,” he says. He leans forward in his chair, mouth curling into a smile as he adds, “I want to be shocked by what people do. I want to be an old fart who is just surprised at what these kids are doing these days.”

Reid-Pharr’s studies initially revolved around 19th century America. However, he entered the profession in the mid-1990s, at the height of the AIDS and crack epidemics — a period that reoriented his scholarship from its prior focus to more contemporary topics.

“I lost dozens of friends, and of all types. Dozens, dozens of people, men and women, young, brilliant people.” His imperative became to produce scholarship “useful in the direct struggle against not only AIDS-phobia, but homophobia, women-hating, anti-black racism, anti-Latino racism, anti-people of color racism,” he says.

He began a collection of essays he decided to call Black Gay Man. The audacity of the title alone invited his colleagues’ censure. Because it was a massive professional risk, Reid-Pharr initially concealed the project from other faculty, often hiding alone in his office to write.

The collection, published in 2001, weaves autobiography and criticism into a meditation on being gay, black, and male, as well as commentary on the state of American society at large. The prose, eschewing the turgidity of many academic works, was praised for its beauty, reflective of Reid-Pharr’s deep investment in aesthetics. For him, cultural production allows people to understand that their humanity is “so much broader and so much grander than the things that oppress us.” Thus, he strives to write “in a way that actually feeds the soul.”

The risks — both in subject and in style — paid off. “After having published a book called ‘Black Gay Man,’ it changed what I was allowed to do,” he says. “It changed what I allowed myself to do.” The well-received collection freed him to embark on a wide range of research projects and presented career pathways that eventually led him to his appointment at Harvard, where he was officially tenured in 2018.

Harvard, which Reid-Pharr expected to be “super, super conservative,” has been a pleasant surprise, he says. As he transitioned into his new position last year, he found himself repeatedly telling a close friend, “People are being surprisingly nice to me.” Reid-Pharr says his friend responded: “Well, maybe it’s not a surprise, maybe they’re just nice.”

At this point in the story, Reid-Pharr swivels in his chair and grows sarcastic: “I thought, ‘What? That’s crazy talk!’”

At the end of the day, it is Reid-Pharr’s students who drive him to pursue his craft. “That’s why I get up in the morning, and sort of rush to class so that I won’t be late, and I’m sweating when I'm getting there,” he says. “I need to impress the students, just because I’m impressed by [them]. I work hard at it because I want to get myself to that standard of what they’re trying to do in their lives.”

It was in this spirit of thriving, and helping those of marginalized races, genders, and sexualities thrive as well, that Reid-Pharr agreed to participate when Harvard called and asked him to be in a promotional video only a few weeks after settling onto campus. When I first mention the video, he leans forward, palms pressed to his forehead with eyes wide, and exclaims, “I know! I’m in it! Oh. My. God.” His voice, ordinarily smooth, staggers, as if — a year later — the call is still surreal.

“The contradiction of it sometimes takes my breath away,” he says of being in the video. “I can’t fix all of that, but I certainly can try to use the resources of this institution to move forward things that I think are absolutely important for our species.” He agreed to be featured for the proverbial high school seniors to show them that, “If that guy can be there, I could be there, too.”

—Magazine writer Matteo N. Wong can be reached at matteo.wong@thecrimson.com.