Harvard’s history is cluttered with ghost stories. Take William James ’69, the namesake of the building that houses Harvard’s Psychology department and the very man who laid that department’s foundations. James was enraptured by the paranormal.

William James is best known for his writings on philosophy and psychology, which frequently appear on the syllabi of Harvard courses. Yet his passion for psychical phenomena — occurrences and abilities that seemingly transcend the explanatory power of natural laws — is less widely acknowledged.

James was committed to the supernatural over the course of his academic career. He co-founded the American Society for Psychical Research in 1885; defended the Society against its many critics; and promoted compelling data on mediumship, telepathy, “extra-consciousness,” and apparitions, some of which he collected himself.

While the field of psychical research has largely been subsumed by progress in its parent field of psychology, traces of its legacy can still be found at Harvard today.

The Personal Becomes the Professorial

James tragically lost his infant son in 1885, the same year he was appointed as a full professor at Harvard. As he and his wife were grieving, his mother-in-law urged the couple to pay a visit to a Boston-based medium named Leona Piper. She hoped Piper might help the couple connect with the spirit of their son.

Indeed, during their visit, Piper was compelled to write down the name “Herrin” — a name James and his wife identified as bearing a striking resemblance to their late son’s name, “Herman.”

{shortcode-643676e3d85b4f5c096d3b981552e3b1ffd480b1}

James co-founded the ASPR that same year, and one of the Society’s main activities was testing those who claimed to have psychic abilities. Though many alleged mediums were debunked as phonies, Piper maintained her credibility.

In an 1886 presidential address to the ASPR, James affirmed Piper’s reputation as a legitimate medium.

“If you wish to upset the law that all crows are black ... it is enough if you prove one single crow to be white. My white crow is Mrs. Piper,” James said.

The activities of the ASPR intrigued Harvard students, and the organization garnered attention from across the University.

An 1888 talk on “Apparitions” from Richard Hodgson, the Society’s secretary, was advertised in The Crimson as time “advantageously spent.”

“[The ASPR] is a society in which the college should be interested because so many of the professors are leading members,” the announcement read. “Among the leading movers in the society the names of Dr. Bowditch, of the Harvard Medical School, Professor Pickering, of the Observatory, Professors Royce and James and Mr. S. N. Scudder, are well-known to most of us.”

Dean of the Medical School Henry P. Bowditch ’61, Director of the Harvard College Observatory Edward C. Pickering ’65, Comparative Anatomy professor Charles S. Minot, and four other College alumni were all founding members of the ASPR who seemingly legitimized the organization.

In 1912, seven years after Hodgson’s death, several affiliates of the ASPR and philanthropists including James’s son — Henry James Jr. — donated money to Harvard and created a named memorial fund that persists today for the study of “mental or physical phenomena the origins or expression of which appears to be independent of the ordinary sensory channels.”

The Case Against Margery

A decade after James’ death in 1910, British psychologist William McDougall came to Harvard to assume the position of Psychology chair.

McDougall had a keen interest in parapsychological phenomena, which was informed by the cultural climate surrounding the aftermath of World War I. The study of spiritualism had grown in popularity as many people grieved the loss of soldiers who fought and died in combat. He was also a noted eugenicist.

In the early 1920s, Scientific American announced a contest for mediums to substantiate their abilities against the test of rigorous investigation, and McDougall was tapped to sit on the panel of judges along with renowned magician Harry Houdini.

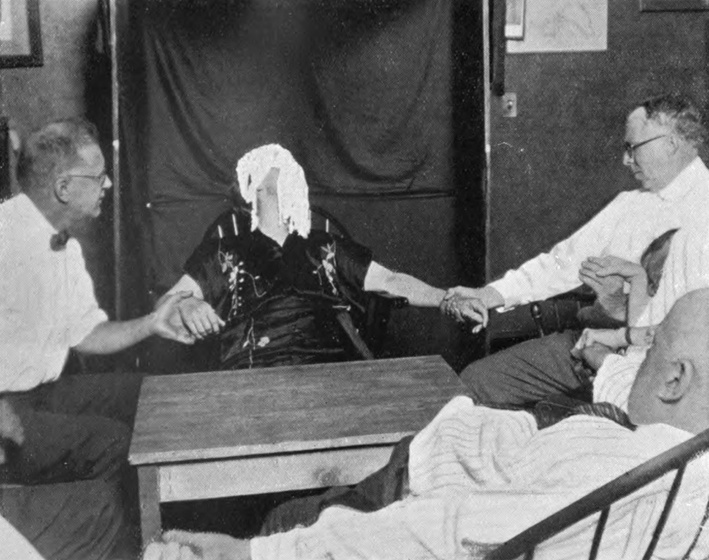

One of the mediums nominated for the contest was Cambridge-based psychic Mina “Margery” Crandon, whose husband Le Roi Crandon was class of 1894. Crandon submitted herself to scrutiny by the Scientific American committee, as well as by a group of 10 Harvard-affiliated students and faculty who took an interest in the local celebrity.

The Harvard group held a series of sessions with Crandon over the years, many in Emerson 11. Crandon would strip and drape herself in a woolen garment before entering the seance room, where she purportedly channeled a spirit named “Walter,” The Crimson reported in 1933. Walter allegedly uttered verses, tugged trousers, pulled hair, and made lights flash and fizzle.

Those in the group initially impressed with Crandon were disillusioned when an amateur magician was able to reproduce these phenomena without calling upon any sort of unnatural powers. Thus, the group’s final 1933 account published in Scientific American became a disavowal of her abilities and was titled, “The Case Against Margery.”

{shortcode-1e3e0e2b71327ab84273e802dcde80349d2d9430}

Despite the ultimate repudiation of Crandon’s abilities, the time and resources devoted to studying her were indicative of serious academic interest in mediums and other psychical phenomena at Harvard. It was during this decade-long golden age that McDougall was inspired to found a “new society” for psychical research in Boston.

"A large, albeit select membership in the society is desired from Harvard University," McDougall told The Crimson in March 1925.

McDougall focused his research efforts on telepathy — a popular topic of inquiry in psychical research. In 1923, he surveyed 1,500 Harvard students for their experiences with the phenomenon. The following year, research fellow Gardner Murphy enlisted a number of students for a cross-continental experiment of thought transference.

Despite all this scholarly productivity, spiritualism would swing out of fashion in the 1940s. Behaviorism — a practice of psychology that studies observable input, observable output, and none of the mediating experience that comes in between — supplanted spiritualism.

Psychology professor Steven A. Pinker says that it has long been a “joke” in the department that a wind tunnel effect around the William James Hall building is in fact the “spirit” of James trying to get inside and protest behaviorism.

‘Mumbo Jumbo’

Psychical research never fully recovered the prestige it once held after behaviorism took hold amongst psychologists.

“Now, the considerations suggesting that it doesn't exist are so strong, that I would say it's a complete waste of time and money to pursue it,” Pinker says.

But others disagree. Parapsychological Association President Dean Radin says recent advances in quantum mechanics — a branch of physics that deals with the strange behavior of particles at the smallest scales — have the potential to refute modern day criticisms of psychical research.

“In [James’s] day, classical physics is the reigning view of the physical world. No one had any idea how you could have things transcend space and time,” Radin says. “Here we are over 100 years later, and our concept of the physical world is built radically different.”

One of these “radically different” ideas is quantum entanglement — a phenomenon in which two particles separated by huge swaths of distance continue to influence each other. Albert Einstein termed it “spooky action at a distance,” and some paranormal researchers have argued that it could serve as a plausible foundation for telepathy and telekinesis.

Pinker, however, does not believe that quantum mechanics has the potential to redeem the field.

“It’s mumbo jumbo,” Pinker says. “They have not spelled out any way in which quantum mechanics could make any difference in terms of what people could be aware of, or what people could cause.”

When the occasional study does support psychical phenomena, Pinker says he thinks it is most likely that researchers employed “fishy statistical considerations.”

But Brenda Dunne — who ran the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research Lab for almost three decades, until it was closed in 2007 — says her lab’s research into psychical phenomena was “rigorous” in its analytic approaches.

“Because we knew that we were under the negative scrutiny, we had to be very, very good and very careful,” Dunne says.

Dunne, who currently serves as the president of the International Consciousness Research Laboratories, says that Princeton was concerned with how the lab’s existence might affect the school's “academic reputation.”

“The university was never particularly supportive of our program. They tolerated it on the basis of freedom of inquiry,” Dunne says. “I think they were rather glad that we ended up closing the place.”

A Princeton spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment.

A Middle Ground

Gary E. Schwartz, director of the Laboratory for Advances in Consciousness and Health at the University of Arizona and a former Psychology professor at Harvard, wrote in an email that, within academia, there exists a “climate of professional (and sometimes personal) hostility” for scholars interested in psychical phenomena.

Schwartz adds that skeptical colleagues will only review his methods under conditions of anonymity because they fear “guilt by association.” This “taboo,” he writes, deters young scholars from taking up interest in the field.

Some particularly adventurous students, however, still manage to make space for their unconventional interests in academia. Samuel T. Moulton ’01, for example, pursued research in psychical phenomena all throughout his undergraduate and graduate years at Harvard.

Moulton says he “got lost in the library and went from psychology to parapsychology” during his undergraduate career. He identified former dean of Social Sciences Stephen M. Kosslyn as a mentor, and wrote his undergraduate thesis — which won a Hoopes Prize — on the topic of thought transference.

“I didn't find anything that was terribly compelling. But I thought maybe I just haven't figured out the right way to inspire this stuff to happen,” Moulton says. As a graduate student in Psychology, Moulton continued his research and published a paper in January 2008 that disputed telepathy.

“I never went into it as a true believer, and I'm not someone that thinks this absolutely doesn't exist either,” says Moulton. “I figured out everything I could do about it, and took advantage of this weird, weird opportunity at Harvard.”

Moulton’s research was financed by the Hodgson memorial fund, which he calls “rumored” and unpublicized.

“It was nowhere to be found online,” Moulton says. “I think I got a very tired looking photocopy of these restricted funds.”

Pinker says the fund has an interesting reputation. “Everyone calls it the ‘Spook Fund,’” he says. “And there have long been efforts to use that money for more respectable scientific pursuits without contravening the terms of the gift.”

The chair of Harvard’s Psychology department did not respond to a request for comment.

Despite the unfriendly climate in academia, Schwartz remains undeterred in his quest to connect the living and the dead through the medium of texting on the “Soul Phone” — a prototype that he is developing in his laboratory.

Schwartz writes that, should the “Soul Phone” be a success, he would hope to collaborate with the spirit of James.

“Presuming, of course, that he would choose to collaborate with me,” Schwartz adds.

Indeed, in a 2010 paper published in the Journal of Consciousness Studies, Schwartz marshalled evidence from controlled double-blinded studies with two mediums to suggest that “[James’s] interest in continuing this work has not waned since he joined the spirit realm.”

Schwartz calls James his “personal hero” — and on this characterization, at least, Pinker agrees. “‘[James] was an all around genius,” Pinker says. “I have quoted him in almost every one of my books.”

— Staff writer Juliet E. Isselbacher can be reached at juliet.isselbacher@thecrimson.com. Follow her on Twitter @julietissel.