You may be a Harvard freshman, but you probably haven’t watched five handsome bachelors vying for your attention, been accused by the Ad Board of publishing the Hasty Pudding Social Club’s Punch Book in The Crimson, and submitted a short story to the Advocate so paradigm-shifting that the New Yorker calls to offer you an internship on the spot.

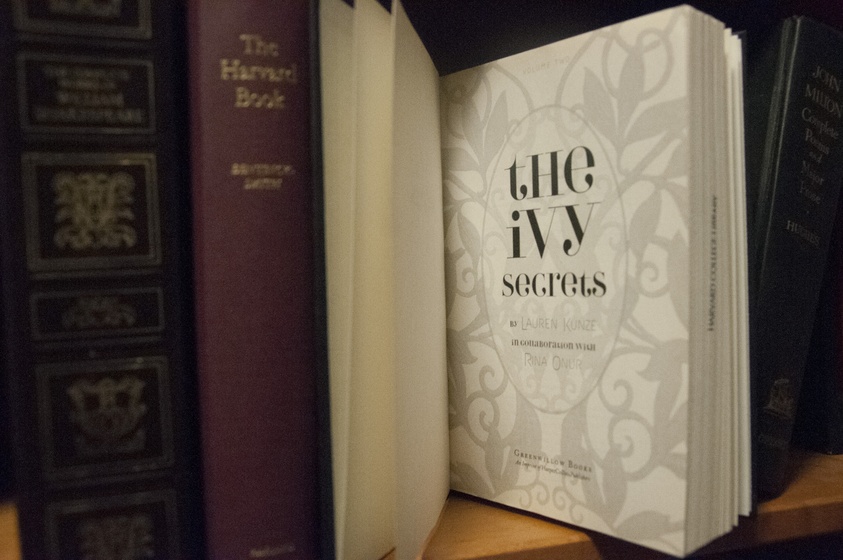

This is, in very rough terms, the plot of “The Ivy,” a four-book young adult (YA) series, published in 2010, that purports to detail the travails of being a Harvard freshman. The series follows Callie Andrews, a suburban Californian trying to find her sea legs in the land of silver-spooned socialites and final club bacchanalias. One of a small subset of YA novels focused on college life, “The Ivy” filters Harvard life through a “Gossip Girl” lens, imbuing the typical first-year Lamont trips and Annenberg dinners with romance, revenge, and scandal.

Lauren E. Kunze ’08 wrote the first book when she was a senior at the College and wanted to see whether she could succeed in supporting herself as a writer. A classmate, Kaavya Viswanathan ’08, wrote a book called “How Opal Mehta Got Kissed, Got Wild, and Got a Life” that used semi-autobiographical details about her Harvard experience to great success — a six-figure advance, an order for a multi-book series, and a movie development deal. Things came crashing down when The Crimson later reported that the book was largely plagiarized. Still, Kunze took other cues from Viswanathan.

“Looking at the market, and what the market was willing to accept from me as a 21-year-old woman in college at the time, it seemed like YA — which I didn’t even know about, I didn’t read it growing up — was the thing that was going to sell,” Kunze recalls.

Kunze attended a talk sponsored by the English department at which an editor from Little, Brown and Company doled out helpful tips to undergrads interested in publishing. At the Q&A, someone asked him if he accepted unsolicited manuscripts. He said no, but gave the caveat that, if someone sent him “a very interesting email,” he’d consider it. Kunze emailed him, and the manuscript got handed around until she found an agent and landed a contract for a four-book series at HarperCollins, she says.

HarperCollins billed the book as a salacious exposé of what goes on behind the closed doors of the nation’s most infamously elitist university. In most of the promotional material for the book, Kunze evaded the question of authenticity with a coy demurre — in her author’s bio, she writes that she “refuse[s] to say how much of it was true.” Clearly, there are some aspects of Harvard culture that Kunze exaggerated for dramatic effect; take, for example, her depiction of Fifteen Minutes as a den of blackmail and sexual intrigue, consumed with publishing articles about whether freshman hemlines are “statistically… shorter than those of the female upperclassmen.”

But many of the series’ more sensational characters and plot devices had roots in Kunze’s actual college experiences. Alexis Thorndike, the fictional Fifteen Minutes comp director and advice columnist who supplies the college with final-club gossip, was Kunze’s favorite to write about (“Like John Milton’s satan,” Kunze said, “who doesn’t love a villain?”). Thorndike is a caricature of Harvard WASP elitism; in a column that opens the novel, she encourages freshmen to eat nothing (“Seriously. Nothing.”) if they want to steer clear of the Freshman Fifteen, and to stick to wearing the “3 ps” (“pearls, Prada, and La Perla.”)

Re-reading this first chapter 10 years later, Kunze is struck by how accurate it was. “I definitely knew people who were really like this,” she explains. “In the social scene that the books focus on — people who were punching — I knew people who were reading Forbes to find out who were the richest people in the class.”

Not everyone was so entranced by this salacious vision of Harvard life. Kunze received some negative reviews, the most stinging of which attacked her personally. “Someone wrote that I was a homely girl acting out my fantasies of having multiple men interested in me,” she says. “Someone else wrote that it was unclear if the author had ever met a smart person.”

Even Harvard publications viewed the series critically. An article in Flyby slammed the book with a review that began “Bored? Not that creative? Simply out of other ideas? Fear not, for you, too, can write a Harvard novel!” Written in 2010, the article links “The Ivy” with other “Harvard tell-alls” like Keith A. Gessen ’97’s “All The Sad Young Literary Men” and Nick McDonnell ’06-’07’s “An Expensive Education.” The list of “Harvard Novels” continues to grow — recent examples include Teddy Wayne 01’s “Loner” and Elif I. Batuman ’99's “The Idiot.”

While many of these titles have racked up highbrow accolades — “All The Sad Young Literary Men” earned a glowing review in the New York Times, and “The Idiot” was nominated for a Pulitzer — perhaps they wouldn’t be so out of place on a shelf next to “The Ivy.” All are love stories, featuring a middle-class protagonist suspiciously similar to the author, who is trying to find his or her way as a fish-out-of-water in Harvard’s culture of elitism and aristocracy. A scene in Gessen’s “All The Sad Young Literary Men” in which the protagonist tries (unsuccessfully) to seduce Al Gore’s daughter could easily exist the same universe as the glitzy clubbiness of “The Ivy”’s Harvard.

Sometimes truth is just as strange as fiction.