Historians call it a “gentlemen’s agreement:” Northern universities, including Harvard, would not field integrated teams while playing against all-white Southern sports teams.

Since the popularization of college sports in the 1890s, Southern universities had pushed to exclude black players from college teams. Segregation in sports went largely unchallenged until the end of the 1920s. One of the first to call for change was William Clarence Matthews.

Born in 1877 in Selma, Alabama, Matthews began his education at the Tuskegee Institute; later transferring to Phillips Academy in Andover. At Andover, he faced discrimination on the baseball team. In a letter to then Andover principal Cecil F. P. Bancroft, one influential alumnus sought to have him removed from the team, unhappy at “the captaincy of the Andover Ball team being held by a negro.”

Matthews subsequently enrolled at Harvard College, becoming the sole black member of the Harvard Baseball Team. Despite his clear talent, an article in the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education says, Matthews was benched in games against the U.S. Naval Academy and the University of Virginia. Eventually, Harvard called off the team’s 1905 tour of Southern schools in support of Matthews.

According to “The Black Matty: William Clarence Matthews, ‘Harvard’s Famous Colored Shortstop,’ and the Color Line”, it was widely rumored that he would become the first black player in the Major Leagues. While this title eventually went to Jackie Robinson, Matthews left Harvard before graduating and went on to become a successful lawyer and political figure in Washington.

Matthews eventually also used his clout to influence the segregated structure of the Major Leagues. “As a Harvard man,” he said to the Boston Traveler, “I shall devote my life to bettering the condition of the black man, and especially to secure his admittance into organized baseball.”

In 1919, Matthews wrote to the commissioner of baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis: “You will note that every other class of people are counted eligible to play in the big leagues. Why keep the Negro out if he can play the same grade of baseball demanded of the other groups?”

Despite Matthews’ trailblazing efforts, the same bias against black talent in professional and intercollegiate sports persisted.

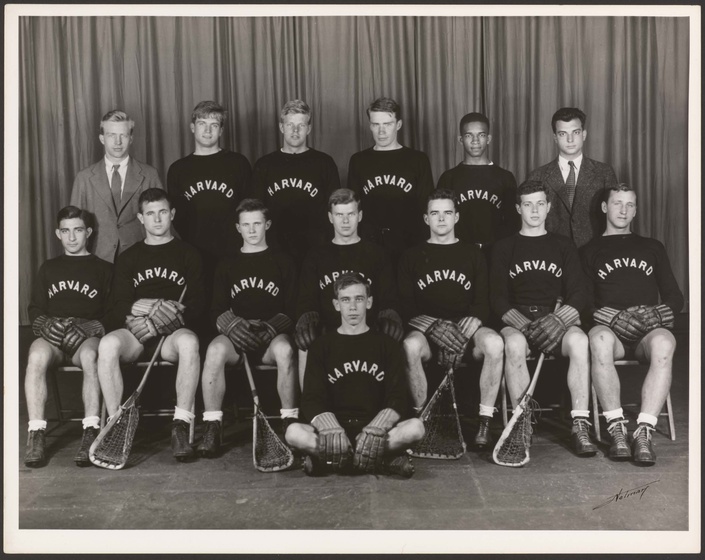

Tensions on Harvard’s campus reached a boiling point in 1941, during a Harvard lacrosse game against the U.S. Naval Academy. Navy’s coach ordered the game off upon realizing Harvard’s team featured a black player, Lucien Victor Alexis Jr, class of 1942. Harvard’s lacrosse coach was unyielding, refusing to bench one of his best players.

Alexis showed up to play despite being warned that “anything could happen.” The head of the Harvard Athletic Department, William J. Bigham, class of 1916, ultimately made the call. Alexis caught a train back to Cambridge that night, alone.

The fallout was swift: Students mobilized, circulating petitions and sending telegrams to their congressmen, senators, and even the President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, class of 1904. The Harvard Crimson ran a series of editorials titled “The Color Line-Up,” which grabbed attention from mainstream publications like the Boston Globe, the Daily Worker, and the Guardian with its bold stance on the issue of discrimination. “If the southern schools wish to meet the northern universities in athletics they should accept the standards of the north,” one article said. “It is not for us to accept their racial discrimination.”

The resounding response forced a historic concession from the Harvard administration: The Harvard Athletic Department pledged never again to bench a player based on race.