{shortcode-9e3d5f3576c96d05573397ae0c25f44a12b8c34f}

Kazuo Ishiguro is a Big Deal, both capitals intended. Following his breakthrough 1989 novel “The Remains of the Day,” he’s kept it up over a career of over two decades with a string of bestsellers. You might remember his last, the heartwrenching “Never Let Me Go,” from its movie adaptation starring the equally heartwrenching Andrew Garfield. His new novel, “The Buried Giant,” is big even by Ishiguro’s standards: It’s his first in 10 years, and expectations are higher than Memorial Church’s steeple.

So when I walk into the church, where the Harvard Book Store is hosting a reading with Ishiguro, the air hums with excitement. There are people of all ages mixed into the audience, although Cambridge’s elderly literati are well represented as always. The couple sitting next to me is having an animated discussion on 1930s radio serials, and ask if I’m familiar with “The Shadow.” (I’m not.) Affronted, they ask if I even own a radio. (I don’t.)

As 4 p.m. draws closer, electricity builds in the church’s carved hollows. The pews fills up fast; people cram themselves in and wait, too excited to push and shove like normal Bostonians. We’re all on pins and needles.

{shortcode-cc5b58f8143e117b00e1a79b67574b4ec13c6e9a}

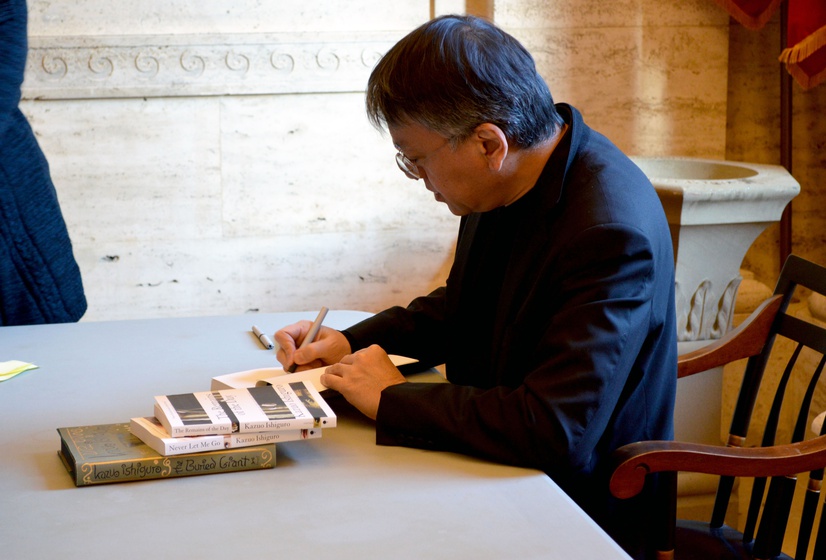

When Ishiguro finally appears onstage, we can’t help but exhale a little. The famous author really is just some guy: average height and wearing all black, with gray hair cut in an unfussy straight line. His interviewer, journalist Robert Birnbaum, shows little flair beyond an unexpected gold earring; he sits peacefully throughout, fiddling with an iPad.

Yet as Ishiguro starts reading from “The Buried Giant,” some of that prior magic starts to return. There’s a careful composure to him that suggests hidden depths, just like his sparse prose. He reads slowly, but as I watch, people’s heads begin to lower in the pews, as if the novel’s first three pages were a sermon all their own.

Watching him, I can’t help think how different he is from the nerdy professor type I had been expecting. In fact, with his all-black getup and effortless cool, he exudes an aged rock-star vibe— and indeed, his first passion was not novels, but songwriting. “I used to sing when I was young,” he admits. “That was a big mistake.” Or was it? Ishiguro may have traded songs for manuscripts, but there’s still a certain measured lyricism to his speech and prose that resembles music.

He’s also modest—almost pathologically so. “I don’t think I have any special insight into the world,” he insists. “I’m not a visionary type of person—just a regular one. And maybe that helps make me more relatable to my readers.” When Birnbaum asks him if he reads his own reviews, he shrugs off the question. “What happens instead is my wife follows me around with an iPhone, reading them,” he chuckles. “And I’m a nervous wreck!”

{shortcode-a143902ad7363faa4ea56ccd5d44102500ba9743}

Birnbaum and Ishiguro make a good team. At one point, Birnbaum flubs his questions and asks the author what it’s like to have been a novelist for 30 decades. “30 decades?” gasps Ishiguro in mock horror, getting some laughs. Later on, when technical difficulties force Harvard Book Store’s staff to euthanize the PA system, the two gamely lean in to share Birnbaum’s shirt microphone.

The PA problems aren’t fixed by the time Q&A is supposed to start. As the Book Store folks freak out, Ishiguro calmly invites audience members to ask their questions from the onstage pulpit mic, which is mounted atop a giant gold eagle. No pressure, right?

One terrified guy stutters out a question about Ishiguro’s use of memory. “The Buried Giant,” set in ancient Britain, deals with an old couple’s quest to regain their memories of past days. “The Remains of the Day” hides tragic recollections of war beneath its smooth depiction of pastoral England. The author seems to return again and again to memory: It lies beneath the surface of his work, a lingering question.

“If we continue to bury big things,” asks Ishiguro, “what are the consequences? When is it better to remember, or to forget?” Although he’s pushing sixty, and by his own admission, is “in his late-stage career,” he seems determined to find the answer. Maybe if we wait another 10 years, he’ll finally share it with us.