Fifty years ago, millions of Americans first heard the news that John F. Kennedy ’40 had been assassinated from CBS’s Walter Cronkite.

Interrupting the soap opera “As the World Turns,” Cronkite’s announcement of the president’s death has since become iconic. A grainy video recording of the newsflash can now be seen on YouTube: “President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time,” Cronkite states, visibly emotional, as he slowly removes his black horn-rim glasses.

Douglas H. Shafner, currently a security officer at Harvard, witnessed the events of November 22, 1963 from a closer vantage point: the master control room of Cronkite’s CBS.

These days, Douglas H. Shafner’s 50-year career in radio, television, and advertising (as well as a short stint driving a Boston tour trolley) is behind him. As a security officer, he is responsible for keeping the buildings up and running at Harvard’s Museum of Natural History and the Soldiers Field Park residences at the Business School: monitoring entrances and exits, and shutting down operations at night.

White-haired and wiry, a Harvard baseball cap casting a shadow over his vivid blue eyes, Shafner takes a break from his post at 60 Oxford Street to recall the day he hasn’t stopped thinking about since 1963.

Shafner describes himself as a moderate Republican more than anything else, but says he was drawn to Kennedy as he hadn’t been to any other politician, before or since. Shafner’s speech grows forceful as he says Kennedy was a pragmatist: “absolutely practical in his solutions to things.”

After Kennedy’s election, Shafner began to read The New York Times religiously. In the 1960s, the Times still published the full text of any presidential speech or press conference; Shafner would read every word. He was astounded by Kennedy’s poise in fielding questions from reporters at his press conferences: “He handed it all with charm and depth.”

On November 22, 1963, Shafner began the morning in the room across the hall from master control at CBS’s operations center, then at Grand Central. Long interested in media—as a teenager growing up in Boston, he was a disc jockey in the heady early days of rock ’n’ roll—he had recently taken a job in the television programming department of a New York advertising agency called Benton & Bowles.

This particular Friday morning, Shafner was responsible for pre-screening an episode of a program entitled “East Side, West Side,” to ensure that there was no conflict between programming and advertising. A technical director from CBS was among the group gathered that morning to watch.

“All of a sudden, the film stops,” says Shafner. The technical director telephoned someone downstairs, Shafner remembers: “And they say, ‘The president has been shot. Come downstairs immediately.’”

Everyone in the room thought it was a joke. “Yeah, he’s telling me the president’s just been shot,” the director said skeptically, Shafner recalls. But when the screening did not begin again, he got a return phone call. If the group didn’t come downstairs immediately, the voice said, the director would lose his job.

Even today, Shafner’s eyes widen and his breath shortens as he recalls that moment of recognition: “Like an arrowshot into my heart,” he says. Dazed and unbelieving, he hurried across the hall to the master control room. This was the final dispatch point, collecting every program and every source—from every studio, every city—before compositing it together and sending it out to television screens around the country.

There he was met by a hectic crowd of programmers, technicians, and other employees all yelling at each other across the room. Within the commotion, a single, still scene: A lead technician, listening intently on his earphones, turns to a production assistant and tells him to find a telop—an insertable slide—at half mast.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Shafner keeps repeating, shaking his head, his hands gripping the swivel chair in a quiet lobby of the Oxford Street IT offices—a sharp contrast from the frantic activity of that decades-ago day.

No one knew for sure whether the president had died or not until a few minutes later. At once, Walter Cronkite, himself down the hall, flickered onto all the televisions in the master control room. “He made the famous announcement: ‘The president has died.’ He took his black horn-rim glasses off,” Shafner remembers, his own voice catching as he speaks, “and tried to brush a tear away.”

But the day was far from over: The next planned programming was the Phil Silver Show, a political comedy that Shafner knew would be far from appropriate for the circumstances. He left the confusion-laden control room, where no one was certain for how long breaking news would remain. Someone screamed, “We’re staying live with news!” as he hurried out the door.

With no cell phone to alert his boss, Shafner had to make the 15-minute trip to the agency on foot. “People were walking around just in shock,” Shafner says. “I’ve never seen anything like it. Nothing like it—this is New York—people in a daze.”

Out of breath, he rushed into the office where several senior vice presidents were gathered around a table. “We’ve got to get out of this—“ he began, to which they replied, “It’s ok—they’ve suspended all programming.”

Another associate, Dick Kirschner, accompanied Shafner back to Grand Central, where they would be responsible for taking any further advertising off the air. They stopped at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, where both knelt to say a prayer. Shafner had to show Kirschner, who was Jewish, how: “He said very quietly, ‘What do I do next?’”

As soon as they arrived at the studio, they were told that the news would be broadcasting live and commercial-free for the rest of the day.

Kirschner went home to Brooklyn, while Shafner stopped in at one of the Irish bars across the street. “There wasn’t a lot of conversation,” he says. “People were just drinking,” and watching the screen.

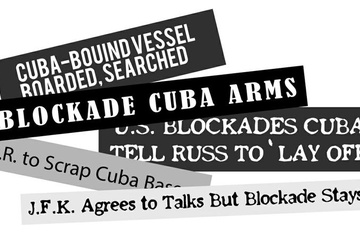

By the time he emerged onto Lexington Avenue, the first afternoon newspapers were ringing the streets, their headlines blaring. The New York Times’ late city edition read: “KENNEDY IS KILLED BY SNIPER AS HE RIDES IN CAR IN DALLAS; JOHNSON SWORN IN ON PLANE.”“

I was born in 1942,” says Shafner, leaning back as he finishes his story. “There’s been major events and assassinations: John Lennon and Martin Luther King—nothing, nothing like this.”

“I felt like the American public was so tied to the hope that he represented,” he adds.The legacy of Kennedy’s shortened presidency has been debated lately, in the press and in classrooms throughout the country. But 50 years later, Shafner hasn’t wavered from his belief that Kennedy’s message was important, and unique.

“Those who weren’t there try to say that he was all surface or style,” says Shafner, his eyes flickering slightly. “He was substance.”

—Staff writer Victoria A. Baena can be reached at victoria.baena@thecrimson.com.