On April 14, 2009, in the middle of the most difficult month of a very difficult academic year, Michael D. Smith, dean of Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, decided to break with decorum. Instead of leading FAS’s regular monthly meeting in the portrait-lined Faculty Room of University Hall, Smith announced that he would hold a town hall-style faculty meeting in Sanders Theatre to lay out, in as much detail as necessary, the implications of the financial crisis that threatened to upturn the biggest, richest, and most powerful division at a university defined by those superlatives.

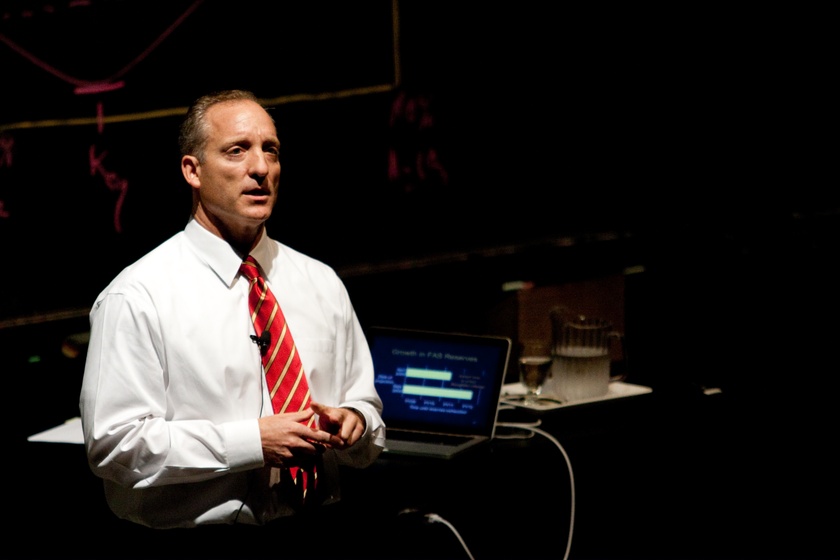

Dressed in shirtsleeves and armed only with a laptop and a stool, Smith confirmed in sober tones what everyone in the jammed theater had suspected for months: After years of dizzying endowment-fueled growth in the University’s professorial and physical footprint, the bubble had burst. Smith’s FAS, a body more reliant on the endowment than other parts of the University, faced a budget deficit that if left unchecked was projected to reach $220 million by the 2010-2011 academic year.

Pressing priorities from the Allston campus to House renewal would have to be tabled, and across-the-board budget cuts would squeeze existing programs. But in just his second year as dean, the Stanford-trained electrical engineer realized he was going to have to go further. Smith informed the faculty gathered in the 130-year-old theater that nothing short of a re-engineering of the entire division, from undergraduate athletics to libraries to the size and scope of the faculty, would preserve the academic mission of the institution.

“I do believe it is extremely important for us to think deeply about how we not only re-size our activities, which is most of what we’ve done today,” Smith told his colleagues with characteristic dispassion. “Now is the time to really start thinking about reshaping these activities.”

Now, four years after announcing cuts, reorganization, and restructuring to the body he leads, Smith has proven himself a remarkably adept problem solver in navigating FAS through the financial crisis. But with the immediate budgetary threats receding and FAS on the precipice of launching the biggest capital fundraising effort in its history, the dean who found himself spending much of his deanship fighting behind the scenes to preserve the Faculty financially must become its very public advocate.

He is undoubtedly among the handful of Harvard’s most powerful figures, overseeing everything from undergraduate life to professorial appointments, but it is unclear what that advocacy will look like and who the advocate himself really is.

Smith, who has recently drawn public scrutiny for his role in last spring’s email search scandal, did not agree to be interviewed for this story. Ever since The Crimson instituted a new policy banning quote review at the start of the 2012-2013 academic year, the person with the most power at Harvard College has not agreed to fully on-the-record interviews with The Crimson, and has not met or spoken with the paper in any capacity this academic year.

Smith’s proponents describe him as a consensus-building visionary, and his detractors see him as a functionary in an increasingly corporate administration. But seven years into his tenure, many members of the community he leads still don’t have a clear grasp on what drives Mike Smith.

THE PRESIDENT’S PARTNER

Broad-shouldered and barrel-chested, the 51-year-old Michael David Smith is not the Harvard dean you always imagined. Though he occasionally dresses in professorial tweed, Smith almost certainly spends more time each week in the Malkin Athletic Center than the Harvard Faculty Club. His square jaw and sharp blue eyes are commanding, and the relaxed, steady firmness of his voice suggestive of an enviously low resting heart rate. In 1999, Fifteen Minutes magazine listed the father of two among Harvard’s 15 hottest professors, and more than 10 years later, only the slight recession in his hairline has altered his looks.

One of the first things colleagues close to Smith mention is that he’s a very good swimmer. As an undergraduate at Princeton in the early 1980s, he not only competed at the varsity level each of his four years, but won the program’s top honor for freshmen and for seniors. While a graduate student in computer science at Stanford, he coached a team of 100 seven to twelve year olds in the sport. And for years, Smith has risen each morning at 5:30 a.m. to swim laps, finishing in time to beat most colleagues into his University Hall office.

There is something about the sport, the quiet diligence and stamina it requires, that maps well onto Smith’s persona. William R. Fitzsimmons ’67, who works with Smith both as Director of Admissions and Financial Aid and on the FAS Standing Committee on Athletic Sports, said that he imagines competitive swimming taught Smith how to allocate his time and energy most efficiently, a skill he says is very useful for the FAS deanship.

“Mike doesn’t waste time on show. He has a remarkable ability to turn in the five directions at once that he needs to turn to, and he doesn’t waste effort or time,” Fitzsimmons said. “It’s like watching a great athlete. Most great athletes, there’s no waste of motion, and he’s not going to waste motion.”

Former Dean of the College Harry R. Lewis ’68 once commented that Smith had “the soul of a swimmer.” The FAS Dean, he said, does not sweat.

Indeed, Smith’s position does not really afford any other option. Look carefully around higher education and within the University, and you will see that there is no real equivalent to the deanship of Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Smith has the last word on all budgets, appointments, academic planning, and personnel issues in an institution that is roughly the size of the entire Princeton University. Theoretically, no Harvard Ph.D. or A.B. can be awarded without his approval. Nor can a professorial hire, promotion, or tenure offer from Celtic to Geophysics, go through without his signature.

Within the University, Smith’s stature is unmatched by his fellow deans. Claiming the biggest budget and the highest profile, FAS forms Harvard’s core, housing the College, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Division of Continuing Education. University President Drew G. Faust acknowledges FAS’s centrality, claiming that no major University initiative can move forward without the involvement of the institution and its dean.

Faust calls Smith a “partner” in running the University—the two have a standing meeting in Massachusetts Hall once a week to discuss the business of FAS. The computer scientist and the historian have remained closely tied to one another throughout their tenures as the two leading figures at the University.

THE UNEXPECTED DEAN

Smith was never supposed to be named dean of FAS. Faust reportedly first offered the job to geophysicist Jeremy Bloxham, the divisional dean for physical sciences. But Bloxham declined her offer, leaving Faust scrambling to find a replacement just six weeks before she took office as Harvard’s new president.

Critics of the appointment are fond of saying Faust’s appointment of Smith a week later came out of nowhere. Indeed, before Faust’s decision, Smith had kept a fairly low profile on the faculty political scene, only intermittently attending FAS faculty meetings and serving on two FAS committees, both of which concerned athletics.

But if he was absent from mainstream FAS politics until his promotion to dean, Smith was rising quickly within the ranks of an institution that was itself becoming increasingly prominent within the University: the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences now known as SEAS. Administrators were in the midst of placing increased emphasis and resources on the once underperforming stepchild of FAS, elevating it to school status in 2007, the same year they picked Smith for the FAS deanship.

Smith arrived in Cambridge by way of Palo Alto in December 1992. First hired as an instructor, the computer scientist entered the prestigious FAS tenure track when he formally earned his Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Stanford the following January.

As he moved up the tenure track—a process he would eventually oversee as FAS dean—the budding computer scientist quickly earned a reputation as a strong teacher and loyal advisor. In a department characterized by young, energetic computer scientists, former students said Smith was notorious for his long hours and even-keeled work ethic.

Omri Traub ’98 took one of Smith’s courses his sophomore year and quickly became close with the young assistant professor, joining his research team and taking him on as a thesis advisor. Traub said he remembers several long nights working to debug code when Smith stuck around until two or three in the morning.

“There was just an ethic [...] always put the student first, and if you do that even if it hurts your personal priorities in the short run, it really pays off in the long run, and I think it really did for him,” said Stuart E. Schechter, who worked on and off with Smith as a graduate student from 1996-2004.

Smith did not have to wait very long to reap the benefits of his popularity among students and colleagues. He was granted tenure in 2000, one of the rare computer scientists to be granted the distinction from within the University. At the time, Smith joined a growing contingent of academics attempting to use their expertise in computer science outside of the realms of academia to cash in on the last legs of the dot-com bubble.

“It was a way for these professors who obviously had very marketable skills to feel like they were a part of this movement that was taking place, to get some part of the action and also be in touch with what’s happening in the industry,” said Traub.

Drawing on his academic research in computer architecture and compilers, Smith co-founded Liquid Machines in the basement of his wife’s Lexington brokerage firm in 2001. The data technology startup promised its customers computing security and later protection against leaks of digital information. Smith served as the company’s chief scientist and chairman, and he and his colleagues raised $40 million dollars in capital for the company in the 10 years before it was sold.

Like a number of other current and former colleagues close to Smith, Traub who went on to work for Smith at Liquid Machines thinks that his former boss’s time in the private sector taught Smith valuable leadership skills.

“Running a startup is a pretty delicate thing,” Traub said. “You have to be nimble, agile, willing to change direction when one idea or line of thinking doesn’t turn out too well. And I think all those years of working with partners and other partners helped prepare him for the deanship.”

Smith soon re-focused his energies on the University full-time, and as he did, his success and profile in the classroom began to grow. In the fall of 2002, he took over the now-celebrated CS 50: “Introduction to Computer Science I,” a course he taught five times. Along with high Q Scores, his course earned the allegiance of students that included the likes of David J. Malan ’99, who would one day succeed Smith as the instructor of the popular course. In 2005, Smith was promoted to Associate Dean for Computer Science and Engineering.

According to Schechter, rumors that Smith was being groomed for a different deanship, that of the Division of Engineering and Applied Sciences, were not uncommon, but Smith never addressed them.

“Ambition seems sort of the wrong term for it,” Schechter said. “Ambition sounds like it is someone who is going to push other people out of the way. He is just the kind of person who is happy taking responsibility that folks to hand to him.”

“For someone as driven and successful, there are a couple ways to get there,” said Kim Hazelwood, another former Smith advisee. “One is to claw your way up. He’s not one to do that. He just sort of excels and people notice. That is the main thing that has led to his success. He just excels.”

ENGINEERING A RECOVERY

From the moment he moved into University Hall, Smith faced a set of extraordinary circumstances that threatened the functioning of the institution no one expected him to lead.

It is difficult to understate the magnitude of the financial crisis that gripped FAS from 2008 to 2011. Nearly every major aspect of Smith’s deanship has been affected by it, from House renewal to curricular changes. So powerful is the crisis-management narrative that has come to animate his tenure, that many forget that Smith had a full year in office before the markets tanked. Much of that first year was spent rebuilding an administration and faculty fractured by the ouster of University President Lawrence R. Summers.

“I think it’s difficult to imagine, to come into this job and be hit by the financial crisis,” said Henry Rosovsky, perhaps FAS’s best-known dean, who served from 1973 to 1984. “They really had no time to settle into the job.”

In the fall of 2008, not long after students returned to campus, the bottom fell out of Harvard’s financial foundation. The University saw its endowment drop by nearly 30 percent, and FAS’s portion plummeted from $16.7 billion to just over $11.7 billion over the course of that year. As the Harvard Corporation—the University’s highest governing body—cut back on endowment distribution, FAS, which relied on such distribution for 56 percent of its budget, was devastated.

Smith, trained as an engineer, attacked the problem systematically, poring over budgetary details while trying to preserve his body’s broader objectives.

“As he always says, he’s an engineer. So he studies the structure, the infrastructure, and he anticipates what will work. He studies the problems and also anticipates those problems,” said Diana Sorensen, the divisional dean for the arts and humanities. “Engineers also know that they have to work collectively to solve problems. No one flash of genius will solve a problem. It takes a team.”

Smith relied on teams of advisors and colleagues in attacking FAS’s budget catastrophe. He appointed six committees to study how various components under his leadership might be trimmed and made more efficient, eventually cutting budgets 15 percent across the board. Faculty searches were slowed, thermostats were lowered, positions were left unfilled, and hot breakfast disappeared in the Houses as Smith tried to meet immediate obligations.

“I think he has had to set up mechanisms for establishing priorities,” Sorensen said. “We never wanted to say we’re shutting down the shop, but we had to balance business as usual with restraint, while at the same time having some territory for innovation.”

In private, Smith began to articulate a three-phase plan. First, ongoing cost reduction and enhancement of current revenue would help plug immediate holes, reduction and restructuring of the FAS administration would follow and reinforce initial cuts, and finally, a broad academic restructuring would put the body onto more sustainable footing.

And, in short, the plan worked. In 2012, Smith announced a balanced budget. No professors had lost their jobs, though about 200 staff members had taken buyouts or been laid off. No academic departments or programs had been eliminated. Financial aid for undergraduates had been expanded, and the opening of Stone Hall this September, a project with which Smith was closely involved, marked the beginning of College-wide House renewal.

“These were unusual times for Harvard after 2008, but we weren’t on bread and water. We actually survived. People were paid salaries. We didn’t dismiss large number of faculty as other universities did,” said William C. Kirby who served as FAS dean from 2002-2006. “So in fact, managing through all of that without any decline in standards, is really quite an accomplishment.”

It would be shortsighted to say that there does not exist a long list of complaints about individual financial decisions. While Smith has indefinitely halted the growth of the entire faculty, personnel increases in SEAS and the physical sciences have left the humanities with disproportionately restricted resources.

International and regional studies centers have also been hit hard, as cuts sold as temporary have become permanent. Last spring, government professor Beth A. Simmons resigned as head of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs in protest of Smith’s ongoing taxation of the institution’s endowment.

“My personal feeling is the financial crisis has been faced, and through a lot of hard work, things are much better so it would be time to start scaling back this process of reallocation,” said history professor Andrew G. Gordon, a former director of the Reischauer Institute for Japanese studies.

A QUESTION OF LEADERSHIP

All that effectiveness came at a price. For all of the credit professors and administrators will give him for weathering the storm of his early deanship, there exists a sense within much of the professoriate that Smith remains removed from the people and interests he aims to represent. Where names like Rosovsky and Knowles still inspire fierce loyalty and fond memories, Smith’s is treated with a more Smithian dispassion.

There is a sense among many that FAS’s golden era, when professors set the institutional agenda and the dean held court at the Faculty Club, has been replaced by an increasingly bureaucratic one. Even Smith’s strongest supporters acknowledge that as the FAS has grown and its administration swelled, the distance between the professoriate and its dean has grown.

“He has a greater concern than other deans with making sure processes unfold smoothly and efficiently and setting those mechanisms in place, which means there is less that is arbitrary,” Gordon said. “It also might mean that there is less stuff and new, bold things being announced from above, which if it was your thing, was nice.”

Smith’s ability to interact with faculty and champion new initiatives was certainly not made any easier by circumstances of his deanship. Dealing with the immediate budget crisis and its ramifications, including the capital campaign, has occupied a disproportionate amount of Smith’s seven-year tenure, but critical observers explain that Smith’s distance is as much a matter of style as circumstance.

“I never got a sense that he was able to articulate a passion for FAS and what that historically has meant, that this is the heart of the University, that amidst all the money and power and prestige of the professional schools, that the Faculty of Arts and Sciences was the core, that things flowed out from the FAS,” said Richard Bradley, a longtime outside observer of the University whose book “Harvard Rules” chronicled the Summers administration. “It sounds hokey, but that kind of passion is something professors want. They want to feel that their dean is on their side.”

The distance seemed to grow largest last spring when, on the heels of the largest cheating scandal in the College’s history, faculty members learned that Smith had authorized secret searches of the College’s resident deans’ email accounts in hopes of tracing a leak of confidential information about the case. The developer of a privacy protection software company stood accused of violating expected standards of privacy.

In the days and weeks after the searches became public, members of the faculty voiced deep concerns about what they viewed as a betrayal of their confidence.

“Such actions are incompatible with the climate of trust [...] upon which the university has been built and upon which its international reputation rests,” wrote 32 members of the History Department in a letter to Smith. “It points to a gap between faculty and administration understandings of our rights and responsibilities in an institution dedicated to fostering teaching, learning and the open exchange of ideas.”

Initial concern over faculty privacy quickly morphed into a broader complaint about the faculty’s communication and relationship with their administrators, Smith chief among them. In May, at the faculty’s final meeting of the year, professors spent nearly an hour airing grievances to Smith. From the decision to move SEAS to Allston to the expansion of the University’s online education initiative HarvardX, professors described a growing “alienation” between decision-makers and those they affect.

Faculty members say that the distance they feel from Smith is exacerbated by poor communication. Faust, who was present at the May meeting, acknowledged that communication within a body as large as FAS is incredibly important especially given the level of change that has occurred in recent years. “There is a lot of anxiety and I think it makes people feel, ‘I need to know now, I need to know more.’ It elevates the need for communication,” Faust said.

While the various challenges Smith has faced during his tenure have constricted his ability to devote significant time to faculty outreach, Faust noted that the implications of the changes that have occurred during Smith’s tenure make effective communication crucial.

“All of those kinds of questions mean that people want more information. They want more certainty, often in a situation when there isn’t certainty,” Faust said. “I think that puts a big burden on any leader, be it FAS, be it me, be it other parts of the University to communicate as effectively and fulsomely as we can, as often as we can, but it still may not be possible to address everyone’s concerns.”

In his own effort to be more communicative, Smith launched a blog, “Diving In,” in early September on which he wrote that he hopes to share his observations, worries, and excitement about FAS.

“I seem to attend countless meetings and events. Why do I feel then, you might ask, that it’s so hard to communicate with our faculty, staff, and students?” he wrote in his first post. Thus far he has posted three times, most recently on Sept. 12.

CLARIFYING THE CAMPAIGN

Standing at a podium in the Old Quincy courtyard on a sunny Friday afternoon in early September, Smith symbolically ushered in an era of growth and renewal for FAS. Four years after the House renewal project was nearly derailed by the financial crisis, the opening of the re-named Stone Hall marked a tangible step forward, out of the holding pattern that the Faculty had been forced to endure.

Smith, dressed in a grey suit and Harvard tie, told students, Quincy affiliates, and donors gathered for the unveiling of Harvard’s first renewed House that the project was a peek into the future of the House system, and what he imagines the undergraduate experience can be in years to come.

Quincy House Master Lee Gehrke, who worked closely with Smith on the test project, said that the dean showed up to almost every meeting throughout the multiyear planning and construction phases of the project, playing a crucial role in honing and then defending the plans amid the financial crisis that threatened to halt them.

“Through the events of today, I hope that you will come to believe, as I do, that House Renewal is our ‘once in a generation’ opportunity to re-envision that core experience while preserving all that the Houses are and what makes them so special and such a Harvard institution,” an animated Smith told the crowd.

As the immediate threats of the financial crisis have faded in recent years, Smith has increasingly turned his attention to capital campaign projects like House renewal that have the potential to dramatically reorder the varied parts of the University he leads.

Glenn H. Hutchins ’77, a member of Smith’s alumni council of advisors and a co-chair of the FAS campaign, described the dean as the FAS campaign’s chief architect and lead promoter. “Mike is a very persuasive personality by his actions, not his words,” Hutchins said. “In other words, in these settings, Mike is not sort of classicly selling. What he’s doing is telling people what his objectives are and what his philosophy is, what his actions will be, and that is very effective.”

Vague campaign goals aside, just what that philosophy looks like and what Smith’s vision is for Harvard’s most prominent body remain an open question to many in the FAS community. The dean has righted the coubut will the management style that helped him do so be enough to move the Faculty forward?

One thing is certain: the answer will come in actions rather than words, and Mike Smith won’t break a sweat.

—Staff writer Nicholas P. Fandos can be reached at nicholas.fandos@thecrimson.com. Follow him on Twitter @npfandos.