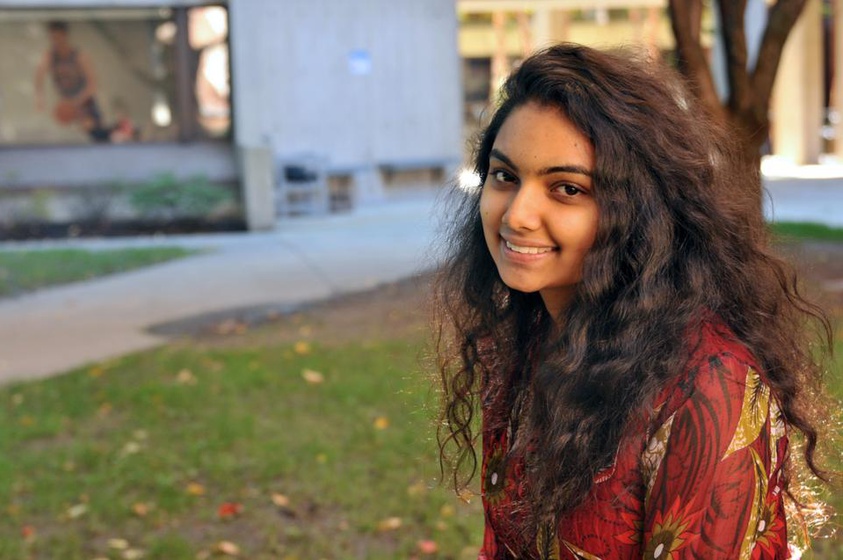

“It’s like a paycheck-to-paycheck sort of process,” says Sasanka N. Jinadasa ’15 as she sits in Lowell dining hall, fingering the small elephant charm hanging from her necklace. “I get a ton of grant money from Harvard, but there is still $6,000 to $8,000 left.”

Jinadasa, who grew up in a largely working class community in Long Beach, Calif., receives approximately $50,000 in aid from Harvard each year to cover tuition, room, and board. But this sum leaves out the other expenses associated with attending Harvard—books, travel to-and-from campus—which she and her family have opted to cover with student loans. Jinadasa, who hopes to work for a non-profit advocacy organization or attend law school after graduation, has personally borrowed $14,000 so far; she expects to have incurred between $32,000 and $40,000 in loans by graduation.

She pauses in her explanation, breathing a little deeper: “I guess it is overwhelming, just knowing that I’m going to graduate with debt.”

Jinadasa is among an increasingly large number of young adults who are struggling to keep pace with the rising price of American higher education. Harvard’s cost of attendance is currently $54,496 annually, and it has been increasing at a rate of 3.5-3.8 percent in recent years. The rate of inflation in the U.S., on the other hand, was 2 percent in September of this year according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If Harvard’s tuition continues increasing at 3.8 percent for the next 20 years, it will cost $114,900 in 2032. If tuition keeps pace with the current rate of inflation, it will be $80,980, roughly two thirds of this amount. Harvard’s peer institutions have been raising tuition at comparable rates to Harvard, though most of them do not come close to providing the financial aid that Harvard does. In fact, Harvard is one of only six colleges in the country that is need-blind and full-need for all applicants (that is, it does not consider financial need in admissions decisions, and meets applicants’ full financial needs). For most Americans, these tuition levels put private postsecondary education beyond reach.

Some—particularly economists—argue that private universities should be even more expensive than they already are.

“If a university is wealthy enough, should it be free?” asks Harvard Kennedy School professor of public policy and management Christopher Avery. “The answer to that is, I don’t think so.” His reasoning: On average, the benefits of a college education will outweigh the costs, and even those graduates with five figures of debt will “catch up very, very quickly.”

“It’s a little bit dangerous to make policy on the basis of what we hope is a long, but temporary, condition of the economy,” agrees Joshua S. Goodman, a Kennedy School assistant professor in public policy.

If anything, Goodman believes Harvard should increase its sticker price to somewhere around $150,000 a year. “Harvard should have really, really high tuition, and it should simultaneously make it as clear as possible to potential applicants that huge amounts of aid are available if their family income warrants it,” he says.

And yet Harvard is not a private for-profit company charging what the market can bear. It is “committed to making educational opportunity accessible to all,” as Harvard stated in the mission published on the admissions website.

Sociology lecturer Patrick Hamm points to this discrepancy, and warns against “subordinating higher education to the principles of the market.”

“Harvard is not a private business. It has its own stated ideals, and it has the knowledge and capability to pursue them,” continues Hamm, referring to the rising costs of a college education.

Despite universities’ public goal of opening the doors to higher education to people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, families who cannot afford their expected contributions are still left with two options: turn down an offer of admission, or take out hefty student loans.

According to the Pew Research Center’s September report on student loan debt, nearly one in five U.S. families currently holds outstanding student loans, and the average debt amount is approximately $27,000, up from $11,086 in 1992 and $17,562 in 2001. (These numbers are adjusted for inflation.) Today’s college students are both borrowing more than ever, and struggling as never before to pay off these loans.

Climbing student debt is worrisome. College costs are increasing at twice the rate of families’ incomes; this generation will graduate bearing more financial responsibility at a younger age.

Currently, around one in seven borrowers has defaulted on federal student loans, a symptom of an educational system that is falling further out of step with the job market. Media, educators, and economists alike are beginning to view these default numbers as a crisis waiting to implode. In February of this year, Standard and Poor’s warned, “student-loan debt has ballooned and may turn into a bubble,” adding that “there are more defaults and downgrades for some student loan asset-backed securities.”

Due to the school’s extensive financial aid program, Harvard students stand largely sheltered from the crisis. Those from lower income families may progress through college with more financial consciousness than their peers, their extracurricular choices limited by the need to pay bills, and their initial employment decisions colored by acute financial concerns. But these students will be graduating from an Ivy League university—they will leave Harvard with most opportunities available to them.

Yet there are students, like Jinadasa, who slip through the cracks. Those whose family circumstances fall outside the scope of Harvard’s financial aid program, or whose parents don’t view college expenses as their responsibility to pay. For them, and for students nationwide, the rising cost of a college education is ever more problematic. Tuition increases are far outstripping the rate of inflation, and financial aid programs—even Harvard’s—are insufficient to keep them from graduating with five-figure debt.

These students’ burdens call into question the current college financial structures, as well as Harvard’s responsibility—as an institution with deep pockets and wide influence—to incite change.

STUDENT DEBT AT HARVARD

“It was something that I knew going into college—or, going into Harvard rather—that I would have to do,” says Kelly A. Sullivan ’14, referring to her need to borrow money to pay Harvard tuition. It is one of those startlingly warm October afternoons, and Sullivan is sitting on the Winthrop House patio, doing homework.

Financial considerations played an intimate role in Sullivan’s choice of school. Ultimately, she chose Harvard, which gave her partial aid, over a small liberal arts college that gave her a full ride. After deciding to attend Harvard, Sullivan sat down with her parents and realized, “Okay Kelly, you can either get paid to go to school, or you can go into debt,” she says. Though Harvard’s aid package was generous, her family still couldn’t meet their burden. Her parents have their own debt, which Sullivan understands. “My parents support me, but they don’t think the entire financial burden of my education should be placed on them, whereas Harvard does.”

The reasons vary—insufficient aid packages, decisions to forgo summer employment for travel or unpaid internships, unique familial financial priorities—but roughly 25 percent of the Harvard student body takes out loans. Though the Financial Aid Office does not have final numbers for current classes, slightly more than 400 students from the class of 2012 took out loans during their time at Harvard, says Director of Financial Aid Sally C. Donahue. Their average debt on graduation was $4,400—a sixth of the national average—and Harvard’s default rate is less than 1 percent, as compared to the national rate of 13.4 percent released by the Department of Education in September.

These numbers are down significantly from what they were a few years ago. “If you go back to, say a decade ago, about 1,000 students graduated with a debt that was much higher than what it is now,” Donahue says.

Harvard’s evolving financial aid program can be credited, in large part, for this decrease. Over the past 15 years, Harvard has been actively trying to change its reputation as a paragon of economic elitism. A series of dramatic increases in financial aid, targeted at students coming from the lowest income backgrounds and eventually the middle class, began in 1998. That year, the University announced a $2,000 increase to all financial aid packages, combined with a promise that outside scholarships could first be used to pay off the personal contribution, before being deducted from the school’s scholarship.

This initial move was followed by a series of expansions in financial aid: In 2004, an income ceiling below which families would receive full aid; in 2007, the removal of loans from aid packages, the allowance that families making $180,000 or less annually would only pay 10 percent of their incomes, and the removal of home equity from aid package calculations.

“We expect families to consider paying for their children’s college educations a priority, but we do not expect them to sell their homes or turn their backs on extended family members so they can pay the college bills,” Donahue told The Boston Globe at the time.

Throughout the economic downturn, Harvard has remained committed to maintaining its substantial financial aid. Harvard has instead cut funding for real estate expansion, construction projects, and job creation. At present, only students with family incomes within the top 5 percent are paying full tuition.

“If I were at any other school with less extensive financial aid, I don’t know how I’d still be in school,” says Bethany A. Harris ’13, who has taken out $14,000 in Harvard loans over the course of her four years.

Other institutions have cut their aid programs since 2008, while Harvard has remained steadfast in its commitment to accessibility. Yale lowered its $200,000 family income ceiling on financial aid, and schools like Wesleyan University have gotten rid of need-blind admissions.

“In some ways, the students who come from the families that are the wealthiest, by paying a high tuition, are subsidizing the enrollment and education of the students who are the least wealthy at the same college,” says Avery. “I’m totally for that.”

But despite Harvard’s generous scholarship offerings and loan-free promises, many students still confront the need to take out loans during their undergraduate careers. The University has an online student loan request form, and within a week, a financial aid officer contacts the student to discuss the process and their reasons for borrowing. Most loans Harvard students take out have an interest rate of 5 percent, and don’t accrue interest while the student is in school.

WHERE IS THE WORKING CLASS?

According to data released by the Financial Aid Office in 2009, about 17.8 percent of students come from families whose income falls in the bottom three quintiles of U.S. incomes. Four percent come from the lowest quintile.

This class breakdown is not unique to Harvard; rather, it is representative of top-tier private universities across the country. In an article from March of this year titled “The Reproduction of Privilege,” The New York Times reported that “74 percent of those now attending colleges that are classified as ‘most competitive’...come from families with earnings in the top income quartile, while only three percent come from families in the bottom quartile.”

These statistics reveal that the university is a long way from realizing the noble goal of “[opening the university’s] doors to students of exceptional ability and promise, regardless of their financial circumstances.” Yet Harvard is hardly a university of balanced economic diversity, and the working class has a minimal presence on campus.

While this underrepresentation seems inconsistent with the mission of a university that aims to serve all students regardless of economic background, it is also emblematic of a systemic problem in postsecondary education. According to a 2008 report published by the National Center for Education Statistics, less than 50 percent of working class parents expect their children to attend college. Often, many of these students don’t even apply. As a result, they’re excluded from certain professional career paths; a reproduction of the country’s rising inequality occurs.

As Anthony P. Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, writes in his book “Rewarding Strivers,” “Americans always have preferred education over the welfare state as a means for balancing the equality implicit in citizenship and the inequality implicit in markets.”

In choosing not to pursue higher education, lower income students are closing off many of their pathways to upward mobility.

The student coordinators in the Harvard Financial Aid Initiative try to address the dearth of working class representation on campus, reaching out to prospective students who might not otherwise consider applying. Jordan L.C. Ashwood ’13, who began working there last summer, says she strives to tell high schoolers that “it’s a very warm and accepting culture here at Harvard with regards to financial aid.”

“I have one parent who I was talking to, and she said, ‘You know I saw this email going out about Harvard financial aid and I thought it was a hoax. I thought it wasn’t real and I almost deleted it,’” Ashwood says, emphasizing that it’s a struggle to make those from the lowest income brackets aware of the realities of Harvard financial aid. “I said, ‘Oh no, I’m so glad you didn’t. It’s definitely not a hoax. It’s very much a reality.’ And so I think this process is just very slow-going, unfortunately.”

Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid William R. Fitzsimmons ’67 says that, though imperfect, the financial aid program does an adequate job of combating inequalities on campus. “One of the reasons we put this program together...is that we really did not want to have an upstairs, downstairs situation where some people had full access to the summer programs, for example, study abroad,” he says. “Or they were into extracurricular activities that might not have been possible if we didn’t have that kind of financial aid.”

But some students don’t see it that way. For Jinadasa, the wealth disparity on campus is especially visible this time of year. “I mean, it is punch season,” she says, punctuating her words with a short laugh.

Given Harvard’s extensive financial aid, there is a certain expectation that these wildly disparate economic backgrounds will be somehow invisible while students are at the College. However, lecturer on sociology Timothy Nelson draws attention to the fact that social class has deep personal roots and will not necessarily fade even if Harvard’s financial aid places them on a relatively even playing field during their time on campus.

“You get these kids here, and then how are you supporting them?” Nelson asks. “In some sense, the administration says, well, we’ve done our job by making the student body diverse. So we’ll throw everyone together without thinking about the forms of exclusion that happen once the students reach Harvard.”

“I wish I could say that it feels like a very classless environment, but it’s just not true. You know who has a lot of money and who doesn’t. It’s one of the first things you find out about people,” adds Jinadasa, her fingers once again moving up to touch her necklace. “I think it kind of does change those friendship dynamics, too. I have a few really good friends who are going to Puerto Rico for Thanksgiving, and they’re like, ‘You should come to Puerto Rico with us.’”

“I’m not going to Puerto Rico for Thanksgiving,” she says.

Harvard can’t eliminate discrepancies in how student wealth is displayed, but Hamm says it has a responsibility to try and lessen the effects. “Harvard is in a position where it can, and in my view should, take steps to mitigate the impact of social class on campus diversity, student admission, and the actual Harvard experience,” he says.

Even for those on the most extensive financial aid, the scholarship does not mean a free ride. “We expect students to work during the academic year, and about $3,000 is the average self-help expectation,” Donahue says. “Most students will choose to have a term-time job and work about 8-10 hours a week to make that up.” Students are also obligated to contribute from their summer earnings, which begin freshman year at about $2,000 and progressively increase.

But 10 hours a week is often only enough to cover what Harvard defines as the student contribution. Left over are personal expenses, the possibility of needing to supplement the parental contribution, or the cost of course books and materials, for which students must decide between working additional hours and taking out loans. On top of that, extracurriculars—from varsity sports that take up tens of hours, to once-a-week mentoring commitments—are also time-consuming.

The result is a campus divided between students whose financial concerns are a daily, pressing issue—with individuals taking out student loans on the extreme—and students whose financial worries are less immediate concerns.

“When they want to go out, I’m working,” says Jinadasa, referring to her friends’ social lives. “My time management has to be colossally better than theirs.”

Harris, whose long blonde hair drapes across the terrier printed on her black T-shirt, says that holding a job while on campus is “a huge time commitment.” She has worked 30 hours a week for the past two semesters in an effort to forgo borrowing more than the $14,000 she has already taken out. This has meant juggling membership in a University Choir and jobs as a ‘Hahvahd’ tour guide and a telemarketer for the Harvard College Fund.

“I often handle it very badly,” Harris says. “If I worked a whole shift and gave a tour that day, when I get home my first thought isn’t, ‘Oh I have to do my reading for Hist & Lit.’ It’s, ‘Interesting, I see they have all the episodes of “Arrested Development” on Netflix.’”

“I also don’t eat lunch almost every day and frequently skip dinner,” Harris adds. “I’ve become a massively good multitasker.”

Still, Harris hasn’t been able to participate in many of the activities that other students find so foundational to their college experiences, such as taking a leadership role in a student organization. This lost opportunity is her “one real regret about Harvard.”

“I’m in shows but I could never produce a show or stage manage a show, which is something that would involve a large amount of time,” Harris says. “I’m not on the board of any organization. I’ve never run for office in anything. I’m not in any other clubs because I just don’t see how I would do it.”

Sarah, another senior who was granted anonymity by The Crimson because her parents do not know about the extent of her student debt, is sitting in Starbucks, her oversized Harvard sweatshirt sloping over her shoulders. Sarah is not from a well-off family. In fact, her parental contribution is zero, and Sarah thinks Harvard generally does a good job with families like hers. “I don’t think there’s a huge need on campus for students on full financial aid to take out loans,” she says. She is one of the lucky ones.

Yet Sarah didn’t get enough funding to do research this summer. In order to be eligible for a loan—and therefore able to pay rent while doing research—Sarah ended up enrolling in a Harvard Summer School course, which she had to borrow extra money to cover. In the end she was left with about $9,000 in debt.

Before this past summer, Sarah had already taken out $6,000 to participate in a program in Spain, and another chunk to purchase a computer. Recently, Sarah also took out a small loan to pay for a semester’s worth of student contribution, which she found herself unable to provide through term-time employment.

“I used to work dorm crew, but I gave that up because I wanted a job where I could do homework,” Sarah says. Now, she works in a library.

Sarah is also pre-med, and had 27 hours of class each week last semester. She feels lucky that the lab where she does research is able to employ her. It’s only possible, though, because Sarah qualifies for work-study, a federal program that helps pay student wages. And Sarah doesn’t mind working. “Where I come from, everyone works while they’re going to college, so I didn’t think it would be such a huge burden on my time here,” she says.

Yet it has been. Sarah rowed crew freshman year, but that was a large time commitment. Now, she has a leadership role in one student organization. “There are definitely things I would’ve gotten more involved in,” she says.

Fortunately for Sarah, her loans won’t start accruing interest until after she leaves school. Since she is applying to medical schools and planning to work as a family doctor in a rural area, that may be years. “Right now, that seems like a lot of money, but I’m hoping after medical school....” Sarah cuts herself off. “Let’s be honest, I’m going to take out even more loans.”

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE ON CAMPUS

Though 25 percent of the student body takes out loans, and even more work multiple jobs to cover expenses, financial burdens are notably absent from the discourse on campus. Students simply don’t inquire about their peers’ economic circumstances and are often reluctant to mention their own financial status.

“I think it’s just sort of assumed that Harvard does such a good job with financial aid that it isn’t an issue,” Sarah says.

Ricardo Medina ’13 had estimated that only 5 percent of students take out loans because he had read that only about 5 percent qualify for the federal Pell grant. He had thought, “If their parents make more than $60,000, then you wouldn’t need to take a loan.”

“I get the sense that—among students—talking about one’s class background as anything other than ‘middle class’ is taboo,” writes Caroline Light, Director of Undergraduate Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, in an email. “This impulse to downplay one’s class status is intensified at Harvard, an institution of high cultural capital and prestige with many students who hail from privileged backgrounds.”

Jinadasa says this is particularly pronounced amongst people on the extremes of the wealth scale. “I think especially people who are wealthy are very, very afraid to discuss money, because they’re not sure who they’re offending,” Jinadasa says. “It’s part of respectability politics, that dialogue: We don’t talk about money; we don’t talk about religion; we don’t talk about politics.”

Medina agrees that students avoid discussing finances, saying that he only really mentions his student loans to his blockmates, and even then, rarely. “I think it’s not just at Harvard. When you’re with friends, you’re not talking about super serious personal issues all the time,” he says. “I think people see it as tacky.”

But silence on the financial front does not mean that students are blind to the circumstances of their peers. Choices of dress, computers, vacations, and eating out are unspoken markers of socioeconomic status, and inevitably lead to comparisons. “One of my frustrations, I felt last spring was that some of my friends were going to Harvard completely free, and when they worked, all that money was going to them, to pay for stuff, to save for stuff,” Sullivan says. “And then I was taking out all these personal loans, and achieving all this personal debt, and all the money I was making went straight to my termbill instead of dinners out with friends. That was a little frustrating for me.”

Hamm, who is teaching a course this semester titled “Inequality, Poverty, and Wealth in Comparative Perspective,” says that discussing these issues exposes vulnerabilities. “One problem people have when they discuss class and privilege is a certain self-consciousness and insecurity,” Hamm says.

“Particularly less-wealthy students might feel that, in order to fit in, they have to downplay aspects of their lives that would reveal their family’s class background, like withholding information or being vague about where they grew up, or where/whether their family takes regular vacations, their work obligations outside of class,” Light writes.

Though Medina agrees that the situation at Harvard is far better than at many other places—his friends back home in California take out upwards of $50,000 to pay for college—his four-digit debt is not insignificant. He borrowed to help pay for personal expenses during a summer spent in Argentina through Harvard, and to alleviate the burden of his student contribution during the academic year. “It’s a lot better here,” Medina says, comparing himself to students at other colleges. Still, Medina finds the promotional material a bit misleading. “Harvard needs to do a better job telling people, ‘No, your education probably won’t be loan-free.’” Nor should it be, some argue. “It’s not obviously a problem that people graduate college with debt,” Goodman says. “The question is how much is a reasonable amount?”

MOVING FORWARD: ONLINE EDUCATION

According to a Gallup survey conducted for Inside Higher Ed, 50 percent of college admissions officers believe it is reasonable for students to graduate from a private four year college with $20,000 - $30,000 in debt.

College is an investment, and like in any investment, risk is an inherent component. Economics professor Claudia Goldin compares paying for a college education to purchasing one’s first home. “No one expects someone to purchase a home from their savings. No one expects them to purchase a home from their income,” Goldin says. “We expect them to take loans out to do that, and they should be long-term.”

Yet with the price of a college education increasing at more than twice the rate of inflation, these debt burdens will soon be far too hefty for families to manage, though for many they are already. Universities, too—especially those with smaller endowments—will struggle to maintain comprehensive financial aid programs.

The question then becomes: Whose responsibility is it to address these rising costs? Should universities be covering costs from sources other than student tuition, like wealthy donors or taxpayers, or should they be drastically reducing expenses from within?

The answer seems to be that both of these solutions are, for the most part, untenable. Universities are expensive because they are, as Goldin says, “collections of very smart people.” She explains that, even though colleges are technologically stagnant, professors’ “earnings have to go up at the same rate of high skilled people in other sectors.”

It is, and will always be, incredibly costly to keep brilliant individuals in academia when they could be making large sums working in other industries.

Government professor Paul E. Peterson suggests that the government is equally powerless to address the rising cost of higher education in an effective manner. “It’s not a matter of what the government does. It’s not a matter of how much the government is going to spend on education,” he says. “This is much a deeper, broader problem than that.”

“The only way education is going to be affordable in the long run is to going to be through digital learning techniques, which are less labor intensive,” Peterson says.

“We are, I believe, on the cusp of enormous technological change in universities. We have been creating courses for which you do not have to be in a classroom, and there are courses for which there are huge economies of scale,” Goldin agrees. “It’s going to be change that’s not just shifting to online education. It’s going to be a mixture of residential living and online education for some, and for those who want it on the cheap, no residential living. That will be moving universities into the dynamic sector.”

We are already seeing this shift toward online education; colleges, both community and top-tier, are developing online course materials that are accessible to a wider audience of students at a lower cost.

With this fall’s launch of edX, Harvard and MIT’s online education platform, Harvard is beginning to move into this space. As of its release, HarvardX has more than 100,000 registered students, all of whom are taking its courses free of charge.

And this shift will by no means be instantaneous. Both the technological developments and the institutional change from within universities will take time. Progress will be gradual.

Online education certainly will not solve all of the issues of the rising costs of higher education. But as colleges begin to adopt a less labor-intensive educational model, so too they will begin to address a crisis that has been a long time coming, a crisis that increasing financial aid or federal loans has been unable to solve. And Harvard will have to be at the center of this change.

As Katherine K. Merseth, Director of Teacher Education Programs at the Graduate School of Education, says, “The institution is one that people pay attention to, and when Harvard talks, people listen.”