When I walked into the first day of Life Sci 2 lab, I was hit with the smell of formaldehyde. Its strong, sticky vapor blanketed my nose. I tried to play it cool, so I pulled out a stool next to a lab bench and sat on my hands. Don’t touch your nose, I said. Don’t do it.

A little while later, we were strapping on latex gloves and dissecting lampreys. Saggital cuts, transverse cuts: we sliced the water creature open. Once it was carefully inspected, we moved on and dissected the dogfish shark. It wasn’t until we had skinned a cat (literally) and started playing around and poking at its muscles that I realized:

1. Dissection is really cool.

2. It’s more common than not.

Not everyone might agree with the first statement, but considering I’m pre-med, it’s a pretty good self-realization. The second idea—the commonness of dissections—is definitely some sort of semi-universal truth. Dissections happen everywhere, and are not necessarily limited to the cold stone tables of the Science Center’s fourth floor. Dissecting things—pulling them apart, analyzing the individual pieces, seeing how everything fits together—is human nature. Objects, situations, people: we pick and pull and prod at them. Sometimes it’s for the better, other times not.

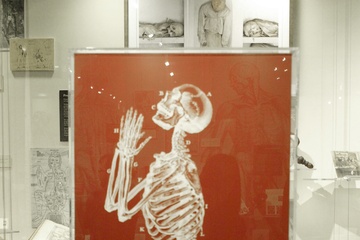

When it comes to animal dissection, LS2 lab is just the beginning of my scalpel adventures. A few years from now, I’ll hopefully be in medical school, sinking my teeth (not literally) into anatomy. I’ve been told that medical students work in groups and develop six-month-long “relationships”—if that’s what you call it—with a cadaver. They journey into our complex physiological world with a few scissors, forceps and blades, and, not to mention, the profound stench of formaldehyde. The thought of seeing human insides doesn’t bother me, but the cadaver-student disconnect does. As students learn about livers, hearts and brains, they gain incredible insight into the human physiological world. But at the same time, they never learn the individual’s life story, family or name.

Dissection is not limited to the realm of biologists and premeds. As I fulfill my sociology concentration requirements, I realize that I’m taught to take the world apart, cut it into little pieces and try to sew it back together. Whether it’s collective effervescence or the historical dialectic, society is also dissectable. Down to its core.

The other day, we read “Connected” by Pfoho housemaster and BAMF Nicholas A. Cristakis. Even though we were assigned to read the entire book, in section everyone fixated on one chapter, specifically five pages within that chapter, concerned with happiness and marriage.

According to the book, married people are happier than unmarried people. Apparently, marriage can extend a man’s lifespan by seven years, but a woman’s by only two. Your risk of death decreases upon marriage, but spikes upon the death of your spouse. This risk for men increases substantially more than that for women. In fact, the risk of death for women varies with their spouses, but not so dramatically. After we discussed the facts, a girl raised her hand and asked a pivotal question—why get married?

The dissection here doesn’t quite mirror that of my cat and doesn’t require forceps, but the general idea is the same. In both situations, we dissect to learn and learn by dissecting. This time, there is no moral dilemma of not knowing the cadaver’s name. Rather, there’s the dilemma of the point of marriage.

Obviously, this is simplified, but just based on the facts, if you’re a woman, why get married? Even statistically, there’s a 50% chance you’ll divorce anyway. I remembered an article about lawmakers in Mexico City pushing for a two-year marriage license that would allow couples to marry, stay together for two years, and then decide to either continue or end their marriage. It’s simple. It’s non-binding. It gets rid of sticky, expensive divorce hassles. But what does that mean for happiness and death? What does that mean for society and culture?

If I mention this quandary to my roommates, we’ll embark upon an hour of dissection. Not of cats or marriage, but of boys and girls and happiness in general. Which is the happier sex? How do we know? We’ll draw on examples of our friends and also people who are mere acquaintances. We’ll try to generalize, come up with our own laws. In a way, we’re all dissecters. Once we’re through, we’ll have our own conclusions, thanks to the incessant prodding we did. We may not be right (no one is running a data survey here), but we’ll have learned something.

Then comes another eternal question—do girls dissect and overanalyze more extensively than boys? Unclear, but I’m definitely guilty of doing so. Maybe we’re unsatisfied with the current answers in the world. Maybe it’s because we have larger limbic systems than men do. Maybe we’re just bored. Either way, I’ve learned a lot from dissection and I still stand by my realizations—it’s our way of looking at the world, and it’s definitely pretty cool.

—Eesha D. Dave ’13 is a socioloy concentrator in Leverett House. She’ll dissect your heart and put it back together again.